Prêt-à-Jouer and Videogame Couture

What happens when we stop thinking about videogames as cinema and instead think of them through other media, like fashion, dance, or architecture?

Note: This paper was originally delivered at the No Show Conference on September 14, 2013. Video of the talk is available online (my bit starts around 20:00 in) if you prefer not to read. And don’t just watch mine—there were many thoughtful, provocative talks given that weekend.

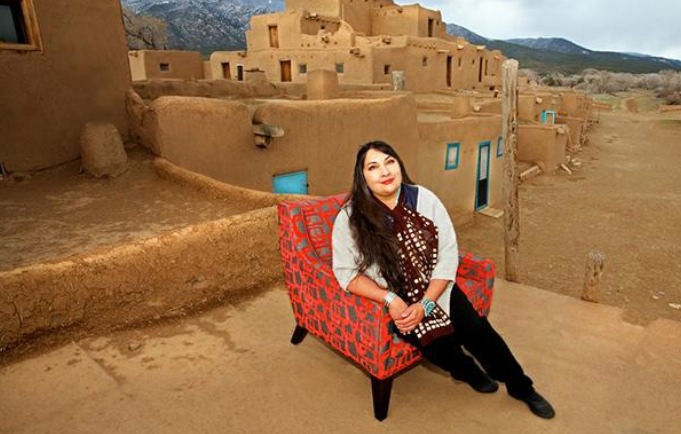

We’re going to begin today with a video clip featuring of one of my favorite media philosophers: Nina Garcia from Project Runway. Here she is discussing a jacket, made by Patricia Michaels—a Native American designer who proved contentious throughout season 11—with co-judges Heidi Klum, fashion designer Zac Posen, and musician John Legend:

http://youtu.be/YKki_0yvooQ

For those unaware, Project Runway is a Lifetime reality show wherein unknown fashion auteurs compete against one another in short, themed design challenges, usually constrained by artificial limitations on time, materials, budget, and contact with their families. Parson’s resident faculty/style maven Tim Gunn presides over the contestants while they toil in the richly-appointed and meticulously-sponsored New York City workroom, serving both as mentor and therapist as they struggle to make cocktail dresses out of duct tape in thirty-six hours.

Runway suffers from the same faults as most so-called ‘reality’ TV programs—trumped-up interpersonal dramas, strategic editing, artificial isolation, and questionable product placement—but it has a core of humanity and creativity often lacking from a genre that routinely fetishizes awful people being awful to others for the voyeuristic satisfaction of its viewers. At its best, Runway is a show about the alternating joy and agony of making things, where the labor of creativity is at least acknowledged rather than attributed to some magical process that everyday artists know simply does not exist.

The judges’ panel we just saw concludes each episode. After the contestants stage their models and send them down the studio catwalk, each outfit receives a peer critique, then the contestants are dismissed so the judges may confer in private to choose the episode’s winner and loser. It’s the same structure recycled for decades now through The Real World, Survivor, and their clones—the loser leaves the island and the victor gains immunity for the upcoming week.

But Runway is fascinating because you get to hear multiple industry perspectives on a single fashion object. Heidi Klum is a model, so she is constantly concerned about wearability; she pictures herself in the clothes and sometimes commissions the designers to make garments for red carpet events or her own commercial lines. Zac Posen is a working designer; he knows fabrics, textures, techniques, manufacturing demands, and other practical elements of construction. Nina Garcia is fashion editor for Marie Claire, so she harps on a look’s ‘editorial quality,’ how it might be photographed, lit, draped, and staged for presentation in a magazine. The fourth judge is always a wildcard, typically another name designer or celebrity known for their fashion sense. Celebrities usually function as market surrogates, giving the designers a sense of whether the elite clientele for whom their fashions are typically made might actually purchase an outfit.

The biggest disagreements arise over designers like Patricia who skirt the line between functional fashion and avant-garde, future-forward garments that may or may not be practical, but push the industry in new directions. Heidi, as we’ve seen, is usually the champion of these designers since she made a career of wearing the cutting edge, while Nina always balks at self-conscious artistry.

She sees every design from the editor’s, advertiser’s, and photographer’s eye—in other words, can this three-dimensional form be flattened into a two-dimensional image that will appeal to my subscribers and ad buyers?

Their brief conversation is a lovely microcosm of conflicting aesthetic theories. John Legend takes, I think, the layperson’s approach to art, asking, ‘Is it beautiful?’ Does it please the eye? Interesting is not enough. If it doesn’t speak to beauty, it isn’t art. Heidi is the high modernist. Beauty is fine, but what she really craves is the new. Patricia’s work is impressive because she ‘always does something different.’ She experiments; she pushes boundaries. Zac is on board with Heidi, but he’s the postmodern critic (and I’ll explain why this makes sense for a fashion designer later), understanding that in the twenty-first century, the new is the old. Art is about ‘bringing cool references,’ quotation, pastiche, hybridization. Nina, meanwhile, is the staunch formalist. She says, in no uncertain terms, ‘Fashion is not art. Stores are not museums. You go to stores to buy clothes. You don’t go to stores to look at clothes.’ So she’s acknowledging the institutional apparatus necessary to validate art. The museum’s role is to set objects apart from function, so we can all become good Kantians and allow our judgment to play with detachment in an artwork’s presence—never touching, only observing.

Nina says, and I’m paraphrasing, ‘Fuck Kant and fuck a museum. I need wearable clothes that I can shoot and sell.’

Needless to say, Patricia did not win season 11 of Project Runway.

So by now you may be wondering when I’m going to get to videogames, or maybe you’re glad I haven’t, so here is a quote to get us on track:

But the problem with thinking about videogames in the way we think about art is, of course, that a videogame is not so disinterested; it’s a business, and in the end, more often than not, the commercial concerns win out over the aesthetic ones. For all that designers would like to be treated as artists and given the respect that they believe to be their due, the majority of them are unwilling to subject themselves to the sort of thoughtful examination of their work that could qualify as criticism, unless, of course, it comes down in their favor.

I’m sure we’re all familiar with this kind of critique of mainstream videogame practice, and many here are actively working to change the perception of videogames, whether through making them or writing about them. This is a good thing. But I’m also concerned about the poverty of both historical inquiry and, for lack of a better term, ‘extracurricular’ media experience we, as critics and designers, exercise when we talk and think about videogames. And I admit that I’ve played a small trick on you and changed two words in the quote to get a point across.

But the problem with thinking about fashion in the way we think about art is, of course, that a fashion is not so disinterested; it’s a business, and in the end, more often than not, the commercial concerns win out over the aesthetic ones. For all that designers would like to be treated as artists and given the respect that they believe to be their due, the majority of them are unwilling to subject themselves to the sort of thoughtful examination of their work that could qualify as criticism, unless, of course, it comes down in their favor.

Holly Brubach wrote this critique in 1992, and it can be found in her anthology of fashion criticism, A Dedicated Follower of Fashion. The purpose of this quote is to hopefully convince you that videogames share many similarities with fashion, more so than many other media, and that this connection can yield fruitful creative inspiration.

We know that videogame designers have long worshipped at the throne of cinema, the apparent gold standard of storytelling, technological innovation, and if they’re really being honest, economic dominance. Because that’s what it’s really about when we strip away the rhetoric of ‘cinematic’ artistry. In a paradoxical capitalist logic, videogames may only be serious art when they make serious money. And what was the preeminent media juggernaut of the late-twentieth century? Cinema. And what is now? Videogames! So we won, right? The industry can let go of its fixation with making games look like movies and just let them do what they’re going to do, right?

Of course not. The desire to mimic cinema continues unabated in game design, from the triple-AAA to the minor leagues. And it’s not just in the realm of storytelling, but more subtly in the structural and formal elements of cinema.

Countless modern games erect a virtual pane of glass, presumably a lens, between the player’s eyes and the virtual world, regardless of whether this makes diegetic sense, as in Metroid Prime, where you view the world from behind Samus Aran’s visor, or not, as with Gears of Wars’ use of the ‘roadie run,’ a camera angle appropriated from embedded war photographers, or even better, clouding the lens with blood spray when Marcus is wounded.

And let’s not forget rainfall, the elemental effect that perpetuates and accentuates the Unreal engine’s propensity for rendering slick, wet textures, so programmers can dot the lens with droplets of materialized cinéma vérité. In indie games, we see other formal clues, like the soft vignetting adopted from early silent films, or more mundanely, depth of field effects.

(And for what it’s worth, Nintendo is one of the few developers that use lens effects playfully and self-consciously, addressing that invisible barrier as the screen itself rather than as a diegetic camera lens. When the ink flowers spit toward the player in Super Mario 3D Land, they do so to cloud the 3DS screen, not a mobile camera.)

In fairness, it’s not all the developers’ faults; the games’ press plays along with cinema worship too. I ran a simple search for ‘cinematic’ on Polygon.com (whom I’ve chosen to pick on since they claim to ‘bridge the gap between criticism and buying advice’), and I found several choice examples from the past six months:

- Tracey Lien’s preview of Titanfall explains how one of the developers’ goals is ‘merging the fast-paced action of multiplayer shooters with the cinematic storytelling of single-player campaigns.’

- Michael McWhertor describes Beyond: Two Souls, the latest from unabashed film devotee David Cage, as a ‘cinematic adventure game.’

- Samit Sarkar assures us that EA Canada tried something new with Fight Night Champion, ‘delivering a cinematic story mode with its own protagonist instead of a user-created boxer.’

- Phil Kollar’s review of the Tomb Raider reboot is riddled with the term: the game shows ‘remarkable confidence,’ as ‘it has all the pieces of a cinematic third-person action title, but it isn’t afraid to give players control and let them loose in large areas’; though he feared the game would be ‘heavily cinematic, low on actual interaction and full of inoffensive but unappealing quick time events’; but thankfully, ‘Tomb Raider still employs some of the cinematic touches popularized this generation, but their execution doesn’t limit players…It’s refreshing.’

Aspiring to cinematic qualities is not bad in an of itself, nor do I mean to shame fellow game writers, but developers and their attendant press tend to be myopic in their point of view, both figuratively and literally. If we continually view videogames through a monocular lens, we miss much of their potential. And moreover, we begin to use ‘cinematic’ reflexively without taking the time to explain what the hell that word means.

Metaphor is a powerful tool. Thinking videogames through other media can reframe our expectations of what games can do, challenge our design habits, and reconfigure our critical vocabularies. To crib a quote from Andy Warhol, we get ‘a new idea, a new look, a new sex, a new pair of underwear.’ And as I hinted before, it turns out that fashion and videogames have some uncanny similarities.

Here’s your concise fashion industry primer, one that I’ve lifted directly from Sharon Lee Tate’s Inside Fashion Design, a standard survey text for fashion students. She says:

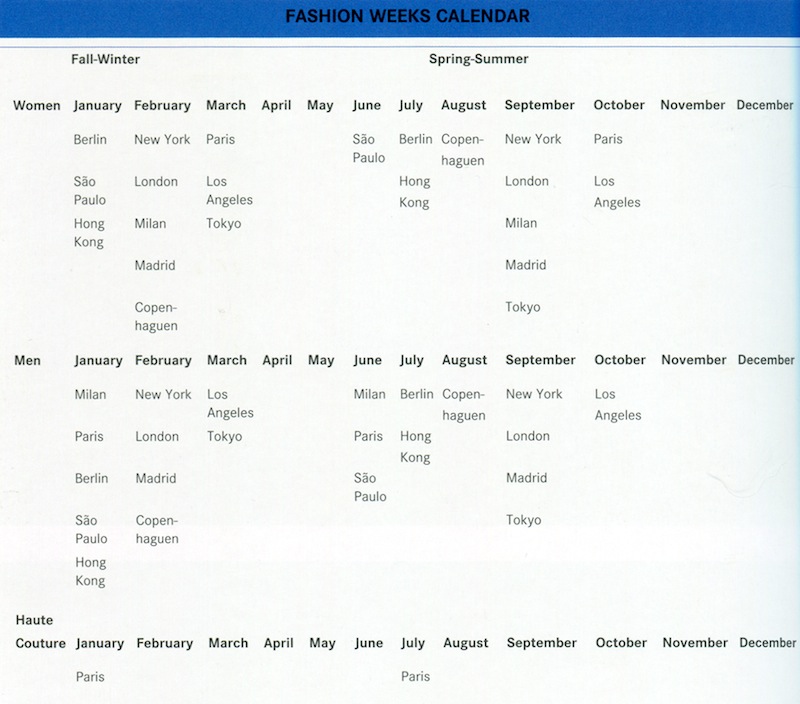

Paris couture and European prêt-à-porter are the traditional sources for fashion trends. Each year at show time, buyers, fashion editors, and manufacturers flock to Paris, London, and Milan to review the new styles…Before the shows begin, U.S. publications preview the opening with articles on fabric trends, rough sketches or style predictions, and interviews with designers. As soon as the shows are over, fashion editors select the styles they feel are prophetic and send photos, sketches, and stories to the U.S. for publication in consumer and trade fashion magazines and newspapers…A flood of fashion predictions hits U.S. fashion publications after these shows. In following months, U.S. editors’ tastes are repeated in photo editorials in monthly glossy fashion magazines. Thus the information is passed on to consumers almost as soon as the designer receives it.

First, a clarification of vocabulary: Couture and prêt-à-porter are French terms that describe both the production and the intended consumer of a particular garment. Couture is hand-sewn and made-to-measure for individual clients, usually women and most definitely wealthy. It is a unique garment, tailored to a specific body. A dress can cost $150,000 or more. It’s the height of exclusivity, and there are regulations in place to ensure this exclusivity; a governing industry commission based in Paris establishes the rules that dictate who may be a practicing couturier. The rules prescribe the number of on-site seamstresses at a workshop, how often they must present new lines to the press, and what types and styles of garments those shows must include. From the late nineteenth century to the 1960s, couture set the standard for high fashion.

Prêt-à-porter, or ready-to-wear, is the next step down the fashion ladder. While still designed for an elite clientele and specific idealized body types, ready-to-wear is not custom-fit for an individual. It draws from both couture and street trends, aiming to set the ‘now’ look for the upcoming season—not just for the mega-wealthy, but for the fashion-forward too. In other words, it’s mass-produced fashion for those who can afford it.

Tate’s description is so interesting because it describes the contours of the videogame industry to a T. Replace Paris, London, and Milan with California, Tokyo, and Germany and you have the three epicenters of the videogame industry: E3, TGS, and gamescom.

And yes, the games press swarm these events to talk about trends, ‘rough sketches’ (aka alphas, betas, and prototypes), style predictions, and designer interviews. They select their favorite ‘prophetic styles’ for the holiday season, which then enter the churning machinery of PR updates, previews, exclusive hands-ons, reviews, and so on. The point is, both fashion and games operate in a cyclic, seasonal mode that we don’t really see in other media. You might argue that Cannes and Sundance function similarly in the film industry, or that summer and winter are the primary release targets for blockbuster movies, but I think there’s something formally distinct about fashion and games, and that is their shared obsession with technological innovation and their own internalized histories.

I don’t think I need to convince you about the videogame industry’s constant pursuit of more better processors with more better memory in the service of more better graphics which apparently translates to more better realism and somehow more better stories. But how does technology play into fashion? Fashion has a longer history than videogames, fabrics are nearly as old as humankind, and even sewing machines have been around since the end of the 18th century. Certainly RAM improvements aren’t affecting Chanel’s spring line in any meaningful way. All true—but technology is a concept we often take for granted when it settles into a quiet cultural ubiquity, when it recedes from our immediate view, like a pair of glasses, a pencil, or a hammer. Fabric, too, is a technology. Cashmere sweaters certainly do not fall off of goats, no matter what Minecraft might lead you to believe, not to mention the extreme processing necessary to transform wood pulp into the purified cellulose fiber we know as rayon.

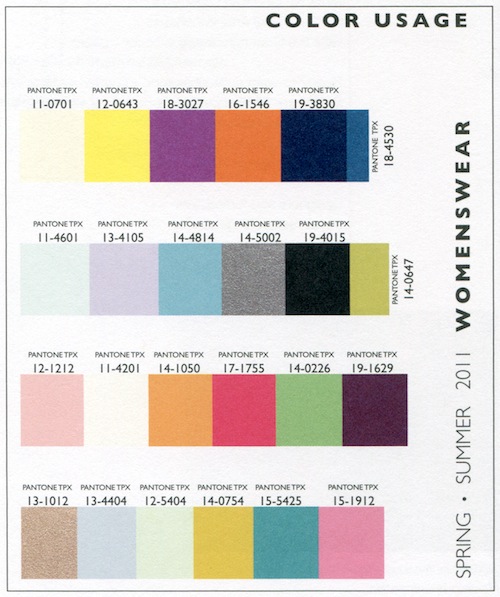

The innovations in fabrics, from their weave and color treatment, to their processing and manufacture, are constantly evolving, often at speeds we commonly reserve for microprocessor architectures. Tate reminds us that design conventionally begins by ‘investigating color trends’ provided by fiber and fabric companies. Based on those predictions, the designer will select their own (hopefully salable) ‘color story’ which then informs their selection of textile lines. Finally, they decide how to incorporate new fabrics with ‘proven fabrications’ to create their collections. In other words, the technology is the starting point for the creative process. Game developers too must first grapple with the platform and tools—be they JavaScript, Twine, the 6502 processor, or Objective-C—before the creative work begins.

The melding of fashion technology and creative design creates an ebb and flow of style that, again, follows the patterns seen in the videogame industry. Tate gives us four markers along the tumultuous road that connects the birth and death of a style. First is the start of a fashion, one that may not catch on immediately because it either originates from a high-priced couturier or develops locally as street fashion. Eventually, this innovation begins to ‘check,’ or sell, and the press will catch wind of an emerging trend.

The fashion then evolves into a staple. It’s hot. Retailers pick it up and the original designer reaps the benefits. But then the knock-offs begin. Substituting lower-cost fabrics drives prices down, making the item accessible to department stores. Prices continue to drop. The style has hit mainstream. The staple transitions to chain store merchandise. Chain store buyers must plan far beyond the seasonal curve, so they opt to buy conservatively, choosing proven items that are guaranteed to sell.

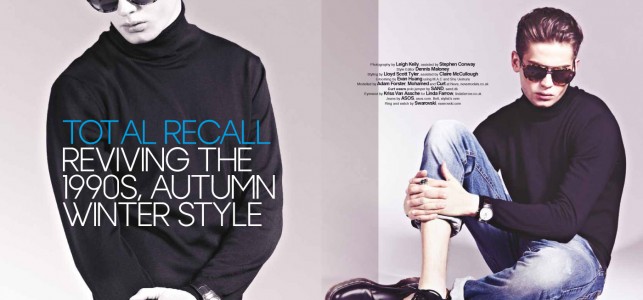

Finally we enter the style’s closeout and demise. Manufacturers employ the cheapest possible fabrics and labor (usually overseas) to shape the styles according to the lowest common denominator of bodies. Fit dies in service of comfort. The style has achieved its widest possible reach. But, once dead, Tate reminds us, the style is now eligible for revival in a decade or two, when nostalgia and our fleeting cultural memory join forces to recontextualize the garment for a new audience.

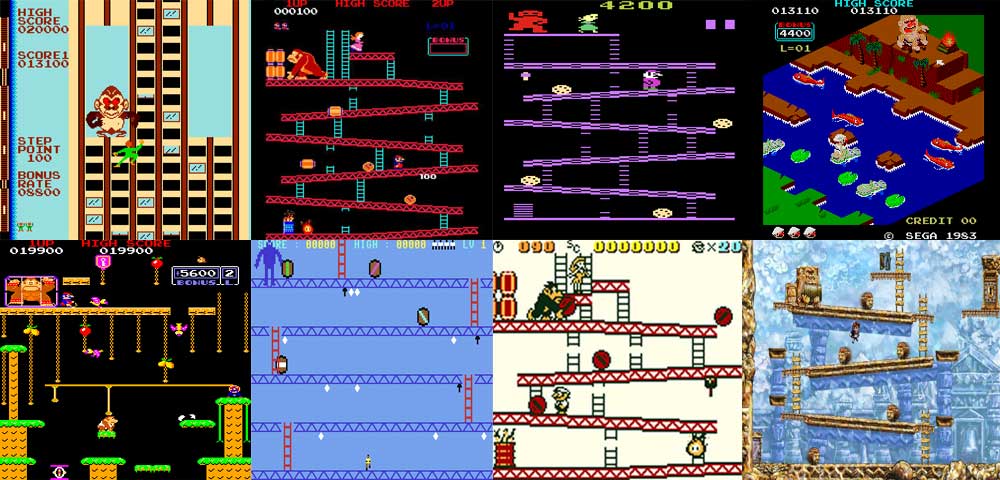

While Tate intends her description to encompass the rise and fall of the miniskirt, turtlenecks, Izod, JNCO jeans, flannel, Doc Martens, and jelly bracelets, it is equally suited to explain the lifespan of the 2D platformer, cover-based shooter, regenerating health bars, pixel art, text adventures, open world games, dual-stick shooters, dancing games, and on and on. The cycle of innovation to replication to sublimation to desiccation to (possible) resuscitation should be familiar with anyone who has kept up with games or fashion for more than a decade. And the longer you’re around, the more predictable these cycles become. As we see the return of acid-washed, high-wasted jeans and candy-colored raver hair, we should similarly expect the second death of pixellated landscapes in favor of chunky polygonal forms a la Final Fantasy VII and Super Mario 64. Depending on your age and penchant for nostalgia, you may cringe or cry with joy at that outcome.

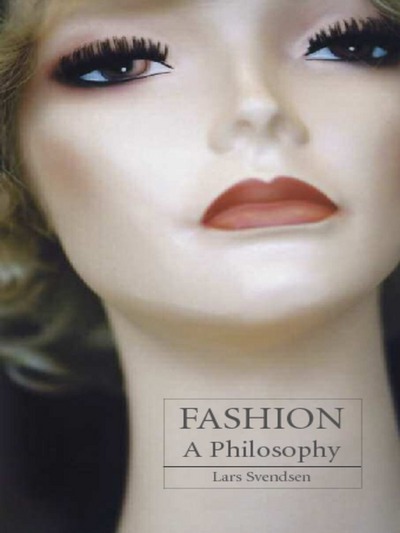

Perhaps fashion and videogames’ intimacy with technology and commerce dooms them to their perpetual non-fulfillment as Art. Lars Svendsen, one of the few philosophers to grapple with the subject directly, claims that fashion is one of the ‘most decisive events in world history, because it indicates the direction of modernity’ and inherits one of its decisive traits: ‘the abolition of traditions.’ But it also rebukes modernity, embracing change purely for its own sake, not for the sake of human progress. He says, ‘Why do skirts become shorter? Because they have been long. Why do they become long? Because they have been short.’

In other words, fashion has no ultimate purpose or goal; rather, it has an internal, contradictory logic that perpetuates itself infinitely and at increasing speeds. Svendson writes, ‘Fashion exists in an interaction between forgetting and remembering, in which it still remembers its past by recycling it, but at the same time forgets that the past is exactly that. And the faster fashion evolves, one would presume, the faster it will forget.’ Fashion devours and shits itself at such velocity that it now lives in a perpetual state of waking amnesia.

Everything is old and everything is contemporary. Fashion fulfills itself only by abolishing itself. As Zac Posen reminds us, it’s the ‘cool references’ that keep us from succumbing to the ‘chic banal.’

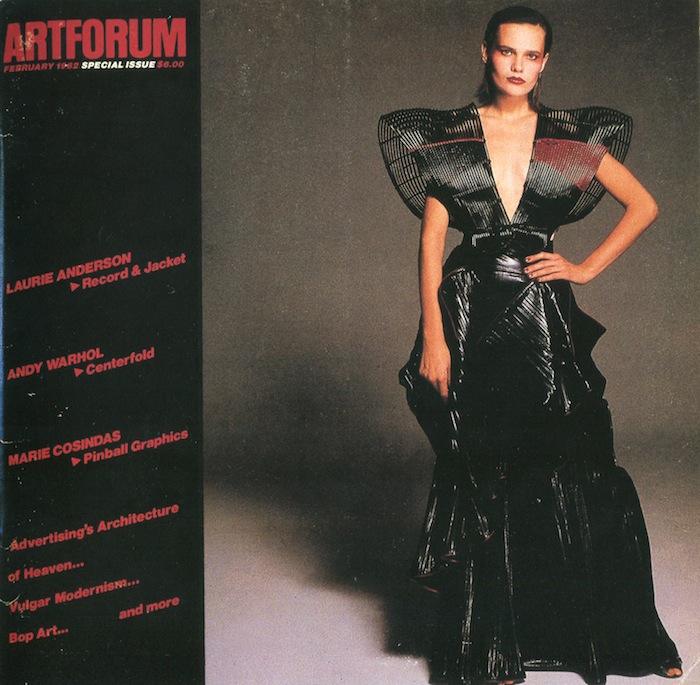

One strategy to break this cycle is to immortalize the contemporary, to make garments that are universal, timeless, Art with a capital A. And since the dawn of haute couture, designers have strived to do so. In the late 1980s and 1990s, this impulse came to a head with self-consciously ‘conceptual clothes’ that were meant more for exhibition than for actual bodies. Fashion even made its way into museums for special exhibitions, usually orchestrated and sponsored by the designers themselves, and ultimately ending up in their own sequestered section of the museum, like the MOMA’s ‘Costume Institute,’ which ensures that Yves Saint Laurent’s Mondrian dress, God forbid, isn’t exhibited beside the actual painting.

This should ring a bell. Remember the victory cries from the videogame community when MOMA acquired several games and consoles…for their Architecture and Design collection?

Mainstream videogames and fashion both share a trait of being beholden to commercial interests, caught, as Svendsen says, ‘in a space between art and capital.’ And despite the utter hypocrisy of the move—lest we forget high Art is big business too—museums tend to shy away from anything with a whiff of commercialism. That can come later, of course, but something must not be created with that in mind. Thus, as Art, fashion and videogames fail from the get go. And if you look at MOMA’s game acquisitions so far, you see a hint of this prejudice at play: Dwarf Fortress, Minecraft, Passage, Canabalt, Myst, Tetris—many, of course, were commercial successes or developed with financial success in mind, but many also have the single-author, auteur-centric authenticity that art institutions desire.

So where are the videogame critics to help the medium’s case? Well, commercialism and technological conquest play roles here too. Svendsen says there is no such thing as ‘critical fashion journalism’ because editorial so closely resembles advertising, calling the fashion press the ‘extended arm of the fashion houses.’

Holly Brubach, who is arguably one of the few accepted ‘critical fashion journalists,’ has the same critique. She writes:

In film, there is a tradition of serious criticism. A director may not be pleased that a critic doesn’t like his movie, but he recognizes the critic’s right to say so. In fashion that right is routinely called into question. Fashion is an art—and therefore deserving of museum retrospectives and thoughtful appraisals—as long as you’re rhapsodizing about its sublime cut and craftsmanship, its ineffable glamour, its impeccable taste. But at the first discouraging word, fashion reverts to being a business, and the writer who doesn’t promote it is castigated for her disloyalty; there is simply too much money at stake.

So videogames and fashion don’t really want what they’re asking for. To raise a game to the level of criticism is to, surprise, subject it to criticism. And when that gets too real, too serious, too thoughtful, too critical, many developers backpedal and say, ‘Hey, hey, it’s just a videogame, pal. We’re only trying to have fun. Why bring up race, or gender, or politics, or sexuality, or class, or anything you can’t quantify in a Metacritic score? We’re trying to bridge the gap, not fall into it.’

And don’t mistake me for saying videogames criticism can’t or doesn’t exist. I would put myself out of a job, for one. Those like Warren Spector who ask, ‘Where is our Roger Ebert of videogames?’ aren’t doing their due diligence. Smart games criticism is all over the place. Critical Distance supplies us with pages of links every week. There’s enough great videogames criticism produced by writers in this room to fill a multi-volume anthology. It’s out there. Just because it’s not collected in the Sun-Times or Rolling Stone does not mean it doesn’t exist.

There are also subtler threads that bind games and fashion. Both are very much about bodies in space, and physicality and gravity, and the texture of materials. We often overlook the importance of touch in our games, the way we hold the controller, the discipline they exert over us, the pliability of our bodies, the eroticisms that happen beyond the screen.

One can wear Shadow of the Colossus much like a pair of Manolo Blahniks.

And the clothes we choose to wear make bold public statements about who we choose to be and what image we choose to commit to, in the same way that the games we publicly affiliate ourselves with, that we choose to examine, that we choose to ignore, structure our identities. One can wear Shadow of the Colossus much like one can wear a pair of Manolo Blahniks.

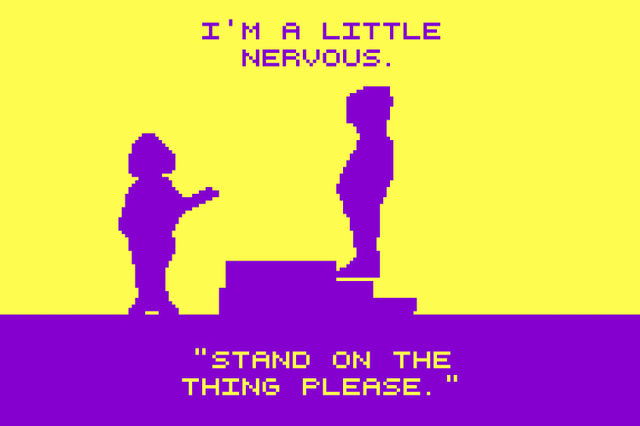

To be clear, I’m not interested in simply trading one media comparison for another. The fashion/videogames connection is not a readymade, 1-to-1 relationship. One point where I think the fashion metaphor strains at the seams is the couture/prêt-à-porter distinction, not because we can’t cite examples of either category, but because the games industry inverts these categories in interesting ways. To me, videogame couture enacts a different class relationship. It doesn’t mean a customized game created for a wealthy elite, usually for conspicuous consumption. Instead, I see game couture as the small, carefully-crafted videogame, usually made by an individual or small team, custom-tailored for a specific, often personal, audience.

As much as I like dys4ia, I don’t think she made this for me or any other cisgender man. I don’t play it as an empathy machine meant to help me experience trans* identity. And though I don’t foreclose the possibility that dys4ia, or any other game, can do such things, Anna meant it for other trans* women considering or going through the same treatments. The rest of us benefit, but we’re not meant to wear her game, the same way we’re not all meant to wear a Dior evening gown.

How about our prêt-à-jouer, the ‘ready-to-play’? One dominant form is Kickstarter and its imitators. Here we find games tailored for a special class of fashionistas, the ‘niche masses.’ If you can find a few thousand fans willing to throw their money into a speculative economy founded on hopes and dreams, all because they really want a modern update to an obscure 90s RTS text adventure originally released for the Sinclair Spectrum, by God, that game can happen. It’s the mass production of fashion, catered to a small but discerning consumer class—ready-to-play for the ready-to-pay.

But prêt-à-jouer also intersects with bigger financial interests. It includes Call of Duty and every other neck stab gun porn simulator and annual sport franchise that tops the NPD charts from year to year. The fit of these games suits millions of players, and they are generally well-cut, trendy, even beautiful.

Prêt-à-jouer is Modern Warfare, but it’s also Super Mario Bros.

In other words, I don’t mean to build in a false dichotomy of high- vs. low-culture practices. Remember that most of us rely on fashion’s base commercial form to clothe ourselves. Prêt-à-jouer is Modern Warfare, but it’s also Super Mario Bros.—and not just the recent ones that feel a bit tired and recycled, but the classics that we adore. If you don’t think Miyamoto is the Isaac Mizrahi of the videogame world, you’re not paying attention to his creative goals. Super Mario Bros. was and is designed with the largest possible audience in mind. I don’t think Miyamoto has spent a second of his career thinking about art or what a videogame is, but rather whether his games are fun to wear. How do they feel? What can a body do in them?

Again, comparing games with fashion does not tidily explain how either works. We have to be vigilant not to trade one media model for another. And we should never ignore the corrosive aspects of fashion that videogames likewise emulate, including the unhealthy objectification of women’s (and increasingly men’s) bodies, the constant disciplining of bodies to technology (whether in high heels, corsets, runway walks, or mascara), the trenchant classism that dictates who can and cannot participate in high fashion, the despicable labor practices that allow me to buy a $7 t-shirt at H&M, the pervasive racism that still determines who walks the runways or is editorial-worthy, and the gross corporate influence tied into fashion that compels Tim Gunn to say ‘Loreal Hair and Makeup room’ or ‘Lord & Taylor accessory wall’ in full every time his contestants need to style and accessorize their models.

The point of constructing a new media model is to embrace more voices, expand the range of what videogames can and should do, and provoke new directions of play that fashion might inspire. I think this same spirit is at the heart of Anna’s call for more videogame zinesters and Ian Bogost’s embrace of videogame snapshots. These cross-media metaphors are a powerful source of inspiration not just for academics, but for games writers and designers too. In The Culture of Fashion, Christopher Breward wrote that ‘in material terms, fashion’s allure was beyond the reach of many; few even in the 1930s could afford the new clothes in the shops. Mothers, sisters and friends hastily put together copies of their clothes with material bought for a few pence a yard from the market or cheap department stores.’ This homespun approach to couture is now taking place in videogames too, thanks to the proliferation of game creation tools like Twine, Stencyl, Gamemaker, Unity, and the like. We need more mothers, sisters, and friends in the community of game creators.

And we don’t have to stop with fashion. Dance, architecture, painting, and poetry still hold untapped reserves of metaphorical power. Games create wonderful choreography. Their rhythmic sequence of patterns and forms orchestrate and coordinate the movements of fleshy, machinic, and virtual bodies alike. New patterns of play can emerge when we think through the metaphors of dance and performance as they apply to games.

http://youtu.be/kGlEqfylbQs

The tool-assisted speedrun, for instance, is one of the more beautiful forms of videogame choreography. Here, games are stripped bare to their algorithmic cores so that a player can construct a meticulous dance with code, rendering objects and time porous and fluid.

One of my favorite French philosophers (because we all should have at least one) is Gaston Bachelard, who wrote a lovely book called The Poetics of Space, a text every game designer and critic should read. He uses the term poetics in its archaic sense, meaning how we make spaces and how spaces make us and what happens to bodies in that process. He spends entire chapters meditating on drawers and bureaus, small spaces where we can keep secrets, cellars and attics, spaces that are mysterious or frightful, cold or dark. He tries to understand the architecture of dreams as real, lived spaces, the kind of spaces that the best architectural games, like Silent Hill 2, Shadow of the Colossus, or Metroid Prime, elaborate and explore, whether to invoke terror, loss, or wonder.

Bachelard talks about the house as a shell that enfolds our being, a place of refuge and safety that we learn as children and forever long to return to. He writes:

Well-being takes us back to the primitiveness of the refuge. Physically, the creature endowed with a sense of refuge, huddles up to itself, takes to cover, hides away, lies snug, concealed.

And the centrality of the home, the refuge, is part of why I think Minecraft has made such an impact. The whole game centers around place-building, a central point from which your virtual being radiates. That’s why your first night in Minecraft is so terrifying. As you stand upon a column of fragile rock and sand while zombies, skeletons, and other twilight horrors lurk below, you feel the full weight of darkness and time as placelessness. No space to call home. No bed to sleep in.

So my modest request is that we leave movies be for now and stop leaning on the crutch of the cinematic. Instead, let’s think about whether we might like to wear a game, or dance with it, or rest in it.