Aperture Science and the Caribbean Orange

I recently visited Chicago for the DHCS conference held at Loyola University College. During the second day of the conference, I was able to sneak away for a few hours and visit the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA). Their featured exhibition was a dual retrospective/contemporary take on minimalism, but I was more fascinated by a small room devoted to a single piece by Gordon Matta-Clark.

The room was filled with photographic documentation, sketches, and preparatory ephemera for ‘Circus’ (or ‘The Caribbean Orange’), a work closely tied to the museum’s history. (In 1978, the museum contacted Matta-Clark about executing a work in the three-story townhouse they were set to first renovate, then assimilate into the museum’s existing structure.) The glass case in the center of the room had a number of hand-written exchanges between museum and artist, from mundane considerations like food and lodging to precise work-related details like the budget for power tool rentals.

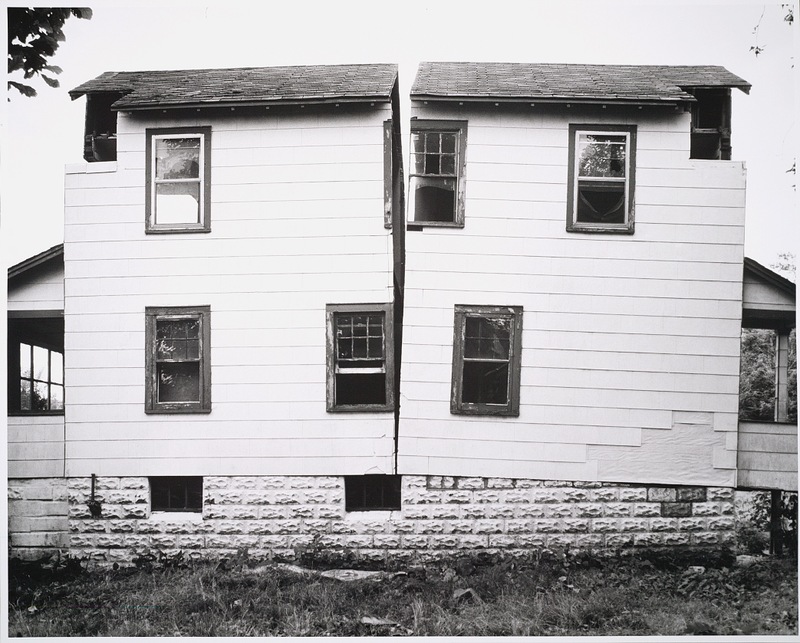

Matta-Clark was known for his building cuts. He used saws, chisels, and other tools to carve away sections of existing architecture, allowing inner and outer spaces to interpenetrate. For 1974’s ‘Splitting: Four Corners,’ for example, he made a straight cut through the center of a (vacant) suburban home, removing part of the foundational support from one end so the house appeared to have a missing wedge.

Matta-Clark variously called his process and work ‘non-uments’ or ‘anarchitecture,’ alluding to the disruptive and destructive act of architectural subtraction. Art historian Irving Sandler calls the excavations ‘a countercultural critique of dehumanized urban renewal and international style architecture’ (Sandler 1996: 69). There was certainly an anarchic spirit to Matta-Clark’s methods – most of his sites were abandoned or forgotten structures that he illegally defaced. And he continually strove to ‘open up’ architecture, in both a literal and figurative sense. Cutting holes in museum walls to join the inner sanctum of ‘art space’ with the outside world is more than mere architectural critique.

Sandler ultimately labels Matta-Clark’s work ‘negative,’ exercises in entropy and futility that trade abandoned buildings for demolished artworks, both equally destined for the rubble heap. I think that’s more Sandler’s yearning for a lasting object than Matta-Clark’s greater project. The materials that have survived in the form of sketches, photo collage, and clever wordplay point to a more positive, even playful, exploration of spatial boundaries than Sandler allows.

And they look a hell of a lot like Portal screenshots.

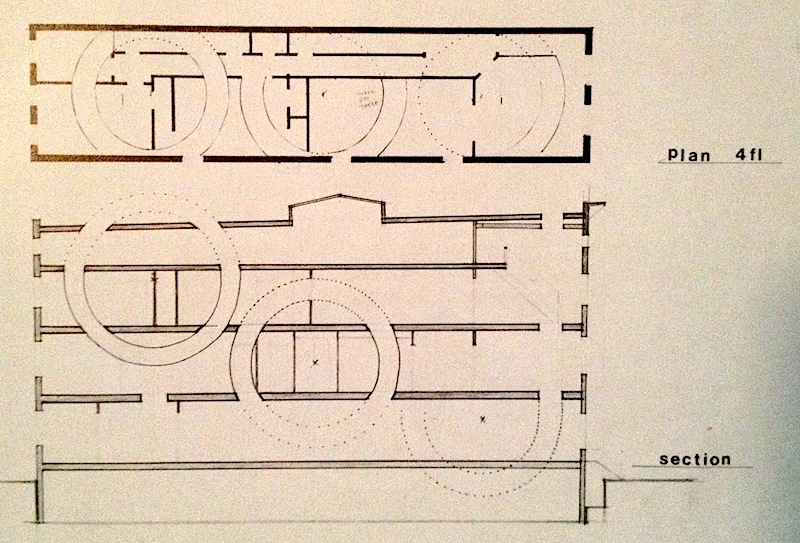

‘Circus’ was conceived and executed as a series of three equal-diameter circular cuts along the diagonal axis of the MCA building. There were also three corresponding circular cuts along the roof’s plane. Their alignment was such that they implied three spherical volumes, a detail punned by the work’s dual titles (i.e., a ‘three ring circus,’ or spherical shapes ‘peeled away’ from the architecture, like oranges).

The anarchitectural result is vertiginous and disorienting. (Literally so. Since this was Matta-Clark’s first museum-sanctioned piece, tours were conducted during its brief exhibition. One of Matta-Clark’s artist friends fell through the floor.) It must have been exhilarating to walk through these treacherous spaces. The careful alignment of cuts created strange windows through rooms and floors. Sunlight and winter cold alike streamed through the architectural displacements. Chicago permeated the buildings interior, and vice-versa.

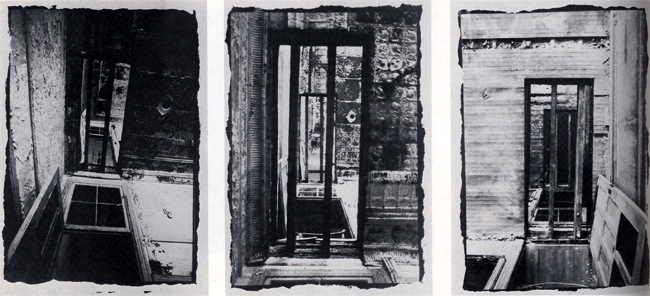

Unfortunately, we can only relive this disorientation through photos. Thankfully, Matta-Clark was a careful documentarian of his own works. This certainly stemmed from the impermanence of his medium, but he also chose to use photography as more than mere supplemental residue. His documentation was an extrapolation of his experiments in real, lived space onto the two-dimensional plane of a photograph.

Matta-Clark cut and arranged his photographic documentation to mimic a viewer’s disorienting experience. In the photo detail of ‘Circus’ below, you can see a body standing on an exposed support beam that crosses part of a circular cut. The left edge of that beam merges into the exposed negative border of another photograph. A third photograph, in turn, is cut to ambiguously overlap the photographic spaces underneath it. They merge and interleave in spatial relationships impossible in physical space, like a fractured cubist castle. Yet Matta-Clark is careful to leave the spokes of the film visible, acknowledging his violation of ‘traditional space.’ It feels like Matta-Clark is having a conversation with his viewer, letting them behind the scenes, as it were, to question how we typically take for granted the ‘three-dimensional’ spaces we experience through photography.

One of the most enthralling aspects of videogames is their ability to play with and submerge players in fantastic spaces. From the non-Euclidean geometries of Atari classic Adventure to the improbable vectors of pipe travel in Super Mario Bros., from the vacant pastoral vistas of Shadows of the Colossus to the verdant natural habitats of Metroid Prime, players are consistently thrust into weird and wonderful spaces.

Much has been written about Valve’s first-person spatial puzzler Portal since its release a few years ago. Its immersive approach to storytelling has rightfully led to the canonization of its characters, dialogues, and – yes – cake jokes. Portal’s protagonist is an (unwilling) test subject for Aperture Science, outfitted with a hand-mounted portal gun that can apparently shoot wormholes through space. Fire your first shot and you see a shimmering oval on your target surface; shoot a second shimmering portal and you create a spatial connection between the two ovals. This mechanically simple system yields absolutely mind-bending spatial situations: shoot portals on the ceiling and floor and you can fall infinitely between them; shoot portals beside one another and you can see yourself emerge from the right portal as you pass through the left. It’s mesmerizing, disorienting, and fun.

When I look at the perplexing open spaces of ‘Circus,’ the sliver of light illuminating the wall in 1975’s ‘Day’s End,’ or the vertiginous door/floor cuts of ‘Doors Through and Through,’ I can’t help but think of Portal’s eponymous space-benders.

Matta-Clark’s works were physical and laborious – he had to rent or borrow heavy-duty tools to extract materials that were never meant to be extracted. The photographs were easier. Cut and paste, manipulate space. But videogames have an interesting advantage. They combine the promise of both of Matta-Clark’s projects: the spatial improbabilities of flattened two-dimensional space with the traversal, exploration, and disorientation of three-dimensional architecture.

But there’s a key distinction between Matta-Clark’s spaces and those in Portal – while the former allows inside and out to bleed together, the latter’s spaces are all interior.

Consider the limitations of the portal gun, beyond its inability to ‘adhere’ to non-prescribed surfaces. Part of Portal’s premise is that you are trapped in a laboratory. The Aperture building (at least what we see) lacks windows, so you are enclosed within a solid cube. You can only ever paste your portals to the interior walls, meaning that you can only ever move within a confined volume. In order for the gun to work properly, you must have a line of sight on both your entryway and your exit route. Without open windows or doors, you can never reach an exterior. In fact, the only time you’re able to escape to the outside is when Glados is destroyed and you’re sucked out through the roof.

But even that ‘exterior’ is a false promise.

If you’ve ever watched a Portal speedrun, you may have noticed some of the clever and confounding tricks players use to escape the confines of Aperture – in fact, violating the basic geometries of the game space itself. Placing portals at surface corners allows you to ‘bump’ outside the map. Travelling outside reveals interesting new vantages. You see the geometry of the map as seen by the developers: thin 3D volumes hung in an empty void.

The artful navigation of this void allows skillful players to sequence break large segments of gameplay, perform faster speedruns, and even access areas previously available only in cutscenes. After you destroy Glados, for instance, you awaken on the outside of Aperture. However, you are no longer in control of your character. You watch through her eyes. The lush blue sky and clouds in the background imply that you’ve finally escaped the confines of the laboratory space. But arriving here out of sequence reveals that the ‘outside’ is merely another ‘non-space.’ The sky is a flat texture – a skybox – like the backdrop at the edge of the ‘world’ at the end of The Truman Show. And even that texture has no exterior relationship to the interiors of previous levels. Each is an independent geometry devoid of any interior/exterior connection beyond its own walls.

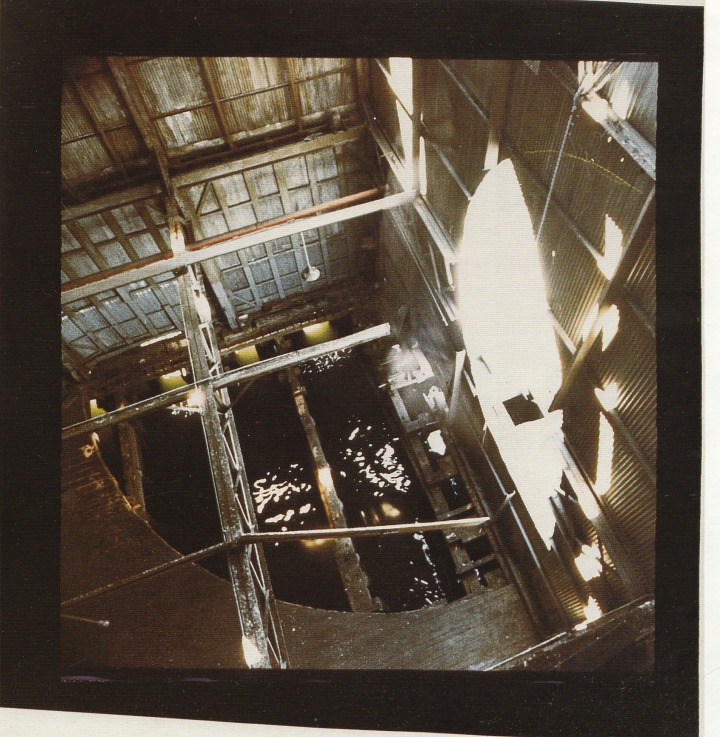

When we compare similar photographs/screenshots from Matta-Clark and Portal, it’s clear that they describe different experiences of space. In the former, architectural cuts below the viewer extend downward to an ultimate bottom, as we see in ‘Office Baroque’:

The same vantage from Portal, in contrast, is only ever staring at the inside, an infinite visual loop between ceiling and floor:

The catch, of course, is that Matta-Clark’s photographs are also a trick. We’re not actually staring into space at all. The photo is as flat as Aperture’s skybox.

Photo Sources:

Matta-Clark photos from: History of Our World, Poul Webb, and myself. (Though I’d guess we all got them from the excellent Gordon Matta-Clark: A Retrospective by Mary Jane Jacob, MCA: Chicago, 1985.)

Portal photos from: Gaming to Learn and Game Player Tees