Bandai’s Joy Family

If you played NES in the 80s, watched Power Rangers in the 90s, or dipped into the world of Japanese toys in the past five decades, you’ve likely heard of Bandai. Established in 1950, the toymaker managed to insinuate their name into the American consciousness like many other Japanese companies of the time—via toys, television, and videogames. Though much younger than the House of Mario, Bandai’s own rise to toy stardom reads like an alt-history version of Nintendo’s. They came of age with model cars and toys at the same time Nintendo shifted focus to the toy and (non-electronic) game business. Like Nintendo, Bandai attempted to capitalize on the emerging videogame market in the 1970s with their TV Jack ball-and-paddle units. They produced pocket electronic games in the wake of Nintendo’s Game & Watch series. They even tried their hand at licensed versions of American consoles, including the Arcadia 2001, Intellivision, and Vectrex—all of which would fail to make an impact in Japan, in part due to the success of the Family Computer—courtesy of Nintendo, of course.

As Nintendo sought worldwide dominance of the videogame market in the 1980s, Bandai played to their strengths as toymakers, bolstering their brand with popular TV, anime, and manga licenses. Ultraman, Dragon Ball Z, Fist of the North Star, Macross, Gundam, Sailor Moon, and Kamen Rider were all among their stable of toys and models. But Bandai’s rise to toy market supremacy began in 1973, when they became sponsor and exclusive merchandiser of Toei Studio’s Himitsu Sentai Gorenger. Twenty years later, the series would cross over to America as the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, one of the most successful children’s television shows of all time.

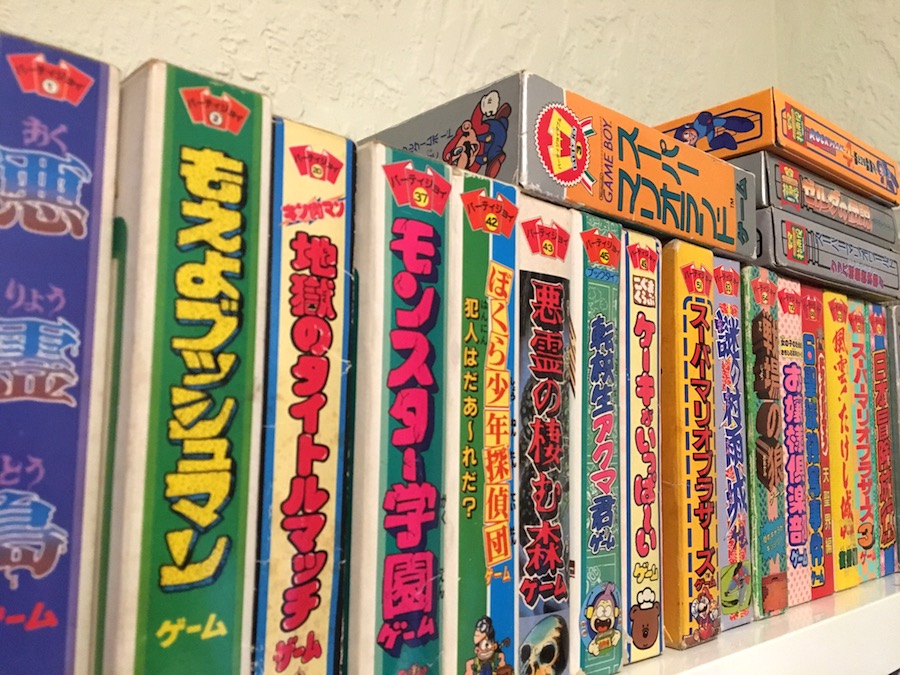

Despite Bandai’s decades of international success, a major part of their history is almost completely unknown outside Japan. Between 1980 and 1990, Bandai released nearly 250 board games under the ジョイファミリー Joy Family, パーティジョイ Party Joy, and affiliated spin-off series. And like their toys and models, these games would feature an impressive breadth of original and licensed characters, from horror stalwarts like Dracula to an up-and-coming pair of action-plumbing brothers named Mario and Luigi. In the U.S., however, Bandai’s board game oeuvre is known only by a few collectors and a handful of entries on Board Game Geek. These omissions overlook not only a landmark in Japan’s board game history, but an important bellwether for changing tastes in popular culture and media during the 1980s.

Old and New Sugoroku

If you trawl Yahoo! Auctions (Japan’s equivalent to eBay) for vintage board games, you’ll often run across the term sugoroku 双六 in the item descriptions. Superficially, sugoroku describes a genre of board game that community database sites like Board Game Geek classify as roll/spin and move. Among game designers, the x-and-move genre is relegated to kids’ game status (e.g., Candyland), because the reliance on luck and random die rolls divests players of any strategic options. In many games of this style, she who rolls best wins. Historically, there is some truth to the claim—in the licensing mania that dominated board games in the 60s and 70s, x-and-move games were the design of least resistance for companies that wanted to capitalize on fleeting media trends.

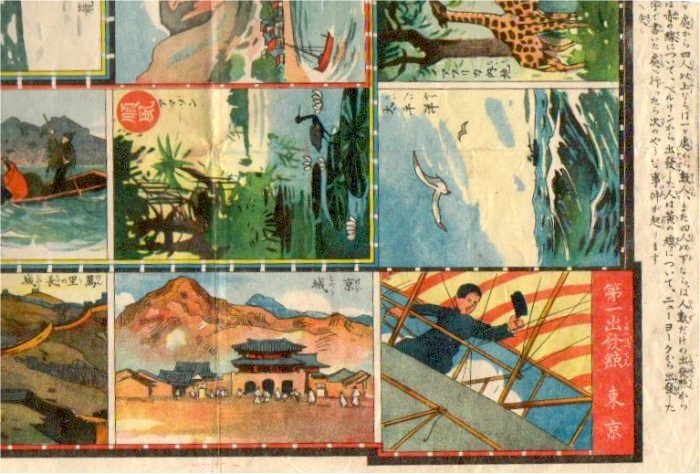

But reducing sugoroku to its mechanical core misses centuries of cultural context. In Japan, the genre traces back to two key stylistic/material variations: 盤双六 ban-sugoroku (or board sugoroku) and 絵双六 e-sugoroku (or picture sugoroku). The former is a Chinese import that dates to at least the 7th century in Japan. An abstract game, ban-sugoroku’s columnar spatial divisions and black & white tokens have clear ties to backgammon, though there are slight rule variations that distinguish it from its ancestor. Like many dice-based games of its vintage, ban-sugoroku waxed and waned in public favor (and legality) due to its associations with gambling.

E-sugoroku, as the name implies, ditched the abstract spaces of ban-sugoroku in favor of vibrant pictorial spaces. These ranged from grids of related vignettes that resemble manga to maps of tourist destinations in Japan. Movement through these spaces could be metaphorical, similar to the slides into moral turpitude in snakes ‘n’ ladders, or representational and literal, for instance, by moving one’s piece from point to point on a real map. Whether literal or metaphorical, in sugoroku, players raced to move their pawns from a starting point along a route to an end goal.

E-sugoroku’s reliance on images tied its growth to technological innovations in printing modes and media. Many sugoroku, for instance, were printed on paper in the ukiyo-e 浮世絵 style during Japan’s Edo period (c. 17th to mid-19th century). In the subsequent Meiji period (1868–1912), improvements in printing technology transitioned sugoroku from rarified to mass media. Magazines in particular became the primary vehicle for sugoroku’s distribution and consumption. Publications would include sugoroku supplements to celebrate holidays, instruct young people, sell products, and more.

Sugoroku’s ties to mass media and printing technology have important implications for how the genre is understood today, as historian Anthony Bryant explains:

Because the game process of sugoroku was moving pieces around a board from one point to a determined exit point, the name “sugoroku” came to be applied to another type of game that should be very familiar to anyone who’s ever played Monopoly, Life, or even Chutes and Ladders. These games in particular were popular among the common townsfolk, as the “playing board” was a printed piece of paper which was cheap, and could be folded up and carried about. The playing pieces could be anything from a distinctive pebble to a coin (the Period equivalents to a little tin top hat, if you will).

One of the most common forms these game boards took was “The Fifty-three Stages of the Tôkaidô,” where each of the possible fifty-one spots between “start” and “finish” depicts a scene of one of the post stations on the great Edo-to-Kyôto trunk road. The start point is at Edo’s Nihon-bashi (station one) and the goal is Kyôto (station fifty-three).

Other game boards include “tours” of famous actors, famous sites and events of the Genpei War, etc. Several post-Period versions are based on events surrounding the tale of the 47 Rônin, and others feature characters in popular contemporary literary works.

Bryant’s quote illustrates how sugoroku is not simply a set of genre or mechanical conventions. Over centuries, the label has come to signify an aggregate of material, procedural, and thematic properties. You can think of sugoroku as “mobile gaming for the people,” i.e., portable, low-cost, quick and easy to play, and tied to popular themes and figures in history, literature, and other media.

Licensed Play

The landscape of Japanese board games in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s looked similar to that of the United States. The advent and unprecedented adoption of television shifted the tenor of games from teaching tools, novel diversions, and sports simulations to cross-media tie-ins that aimed to leverage the fleeting popularity of TV shows and stars. As Polizzi and Schaefer wrote in Spin Again:

Between 1948 and 1958, Americans spent over $15 billion on television sets. As television infiltrated the national psyche, game companies worried that this new “toy” would edge out family game-playing. Little did they realize how revolutionary and positive it would be for the toy industry: inspiring board games and offering an entirely new forum for reaching their true customers (kids!) directly by advertising during their favorite programs. (13)

During television’s pre-regulation era, advertisers could target children directly. In Millenial Monsters, Anne Allison notes how Bandai aggressively capitalized on TV’s popularity in Japan:

Instilling this appetite in children and (re)producing them as avid and future consumers was driven directly by toy companies like Bandai that, by taking over the sponsorship of children’s television shows starting in the 1970s, crafted “money shots” on the screen that would translate, directly and repeatedly, to the desire to buy (their brand of) toy merchandise.

Bandai’s board games naturally followed this strategy, leveraging many of the licenses the company had used for their models and toys.

Among Bandai and its publishing competitors, there was a concurrent shift in the target demographics for board games. What was once the exclusive province of families or children was broadened to include new, and specifically older, players. Bandai’s awkwardly named Game for Adult “if” series (i.e., “What if you played as X in this historical battle…?”) and competitor Epoch’s SLG (i.e., Simulation Games) series shared lineage with both the rules-heavy wargames of American hobbyists and 3M’s groundbreaking, adult-marketed Bookshelf Games. By the end of the 70s, game companies were realizing that adults, university students, and other mature audiences might enjoy games among their peers (or independent of their children).

In short, while Japanese board game publishers were mirroring trends in Western games, they offered a unique cultural spin on licensing and marketing. Where the U.S. veered hard toward D&D-inspired fantasy roleplaying in the 70s, Japan leaned more toward homegrown sci-fi and folklore like Macross or GeGeGe no Kitarō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎). Japanese board games adopted familiar models but filled them with different content.

The Affordances of ¥1,000

These prevailing trends set the context for Bandai’s Joy Family series, which debuted its first games in 1980 (see note below). The series’ first games covered a range of pop cultural subjects, including horror (ドラキュラゲーム aka Dracula Game), travel (JALPAK 世界一周ゲーム aka JALPAK Around the World Game), manga (Dr.スランプ アラレちゃん ゲーム aka Dr. Slump: Arale-chan Game), and even one of the first videogame licenses (クレイジークライマー aka Crazy Climber). Though ostensibly oversized sugoroku, Bandai’s Joy Family games featured numerous and varied components, colorful art, strong visual design, and novel uses of diorama-like 3D features (many that harken to U.S. board game manufacturer Ideal’s toy/game hybrids of the 1960s). And by all accounts, the Joy Family series was an early success. One of its first games, 1980’s Haunted House おばけ屋敷ゲーム, for instance, features heavily in Japanese popular press histories of board games and had a reissue in the early 2010s.

A Note on Dates and Titles

There are nearly no English sources for Bandai’s Joy Family releases. I’ve derived dates and titles from both primary sources (i.e., buying the games and checking their copyright dates or finding images online) and secondary sources (e.g., Japanese books, blog posts, interviews, etc.). Since my Japanese is elementary, many translations are machine-assisted or rely upon English text printed on the games themselves. When dates are indecipherable or unlisted, I rely on available context clues. Bandai’s logo, for instance, had four distinct designs between 1980 to 1990, so it can provide approximate date ranges. In sum, this is difficult and time-consuming work. The language barrier is steep, and, perhaps worse, Yahoo! Auctioneers have a predilection for blurry, off-axis photos that obscure important text or dates. So if you see any glaring errors or you can help with clarifications, please let me know.

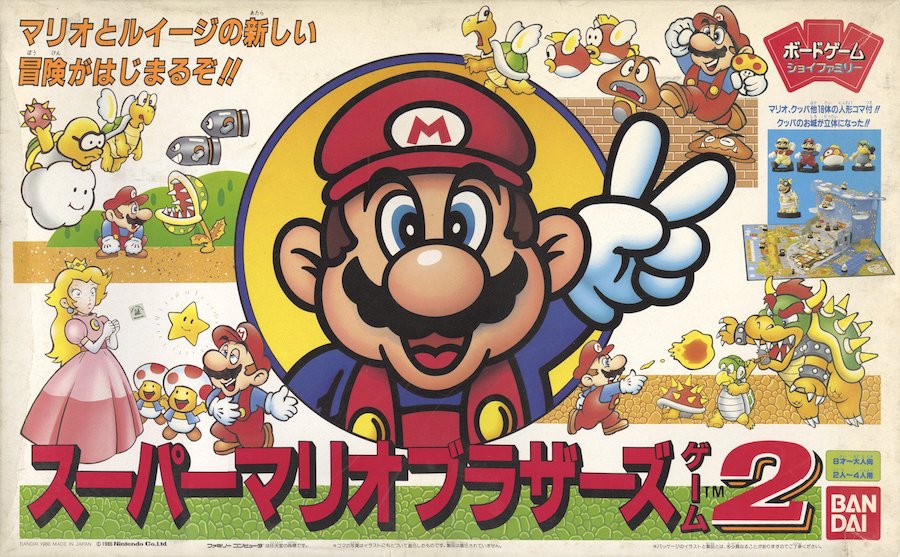

Joy Family games were noticeably larger than their U.S. contemporaries. The standard Milton Bradley box in the 1980s, for instance, measured 19 x 9.5 x 2 in. (48.3 x 24.1 x 5 cm), while the Joy Family version of Super Mario Bros. 2 (スーパーマリオブラザーズゲーム2) from 1986 measured 20 x 12 x 2 in. (50.8 x 30.5 x 5 cm). Similarly, unlike standard single-fold U.S. boards made from chipboard backed with buckram, Joy Family boards were made with a lighter card stock, printed on both sides (with a manga or other illustrated text on the verso), and, in lieu of a flat center fold, folded into a J- or U-shape that wrapped around the game’s interior components. There was often a colorful sliding drawer box (for storing pawns, dice, etc.) that fit the box height- and width-wise. The lighter board construction and standardized storage/component construction must have eased production costs, a trait inherited from the mass media sugoroku found in magazines decades prior.

Joy Family games had strong branding from their inception. Early boxes featured nearly full-size artwork on the cover with a white band along the right edge. At the top of this band was the Joy Family logo: three fanned, red playing cards superimposed by two lines of katakana text, ボードゲーム (board game) and ジョイファミリー (family joy). (Why fanned cards? Interestingly, four of the earliest Joy Family games I’ve found read カードゲーム, or “card game”, rather than “board game” in the logo text, despite being games with boards. Based on the limited contextual evidence I have, my only guess is that these games appear to have used cards, rather than spinners or dice, to dictate movement around the board. Perhaps Bandai considered this to be a novel mechanic for sugoroku.) The logo was typically “Bandai red”, though it could change according to the game’s design.

Depending on their complexity and construction, Joy Family games cost roughly ¥2,000–¥3,500. If this historical currency calculator can be trusted, that range in 1980 equates to about $15–25 in 2015 dollars (though the yen appears to have been much weaker vs. the dollar at that time). For Joy Family’s intended audience of “8 to adult”, that was a pretty reasonable amount. If you were shopping at Target today, you’d spend a little less for Monopoly and a bit more for Settlers of Catan.

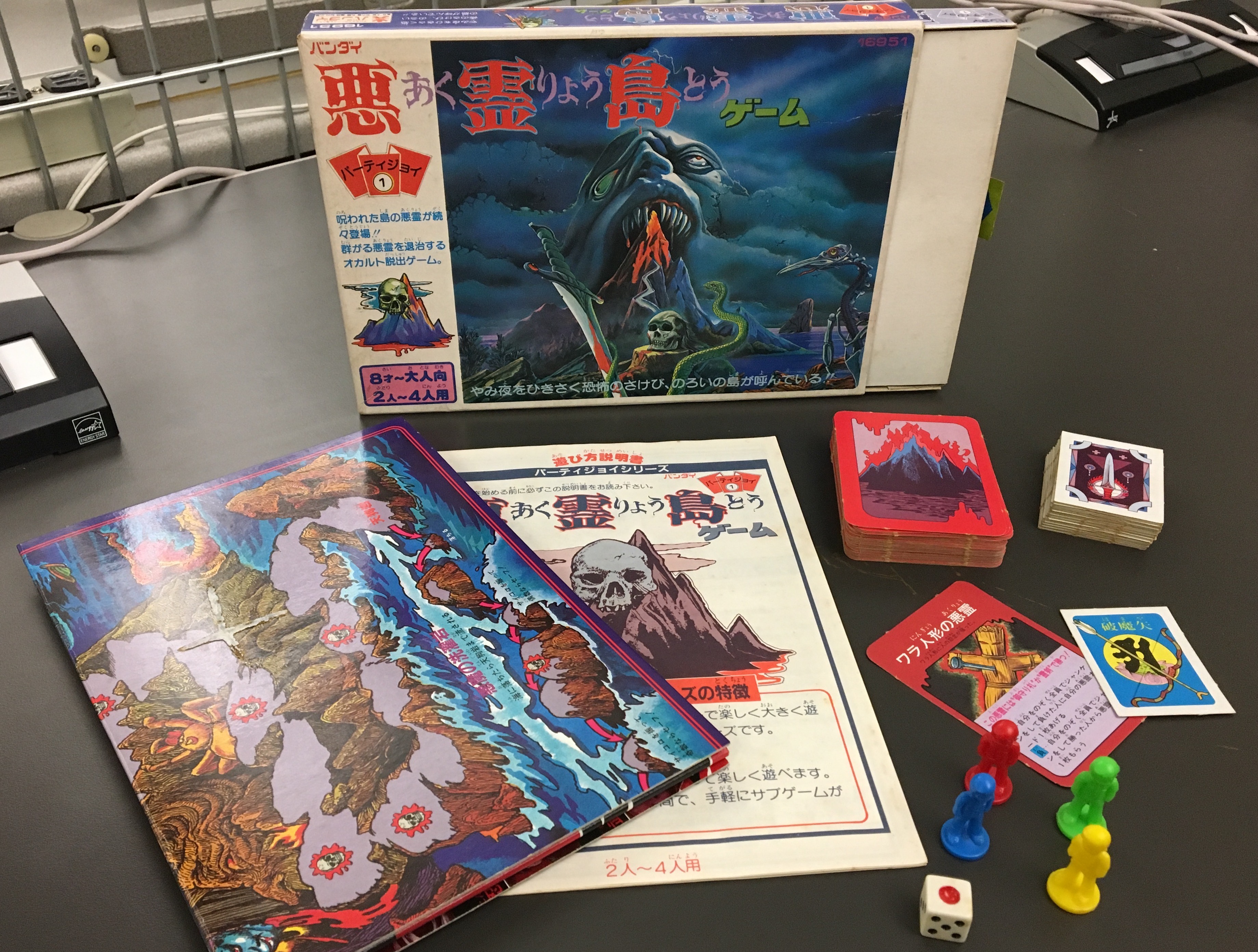

However, Bandai’s true price breakthrough happened three years after Joy Family’s debut. In 1983, the Party Joy series number 1, 悪霊島ゲーム Demon Island inaugurated a breakneck, eight-year stretch of continual board game releases. Priced at a uniform ¥1,000 (~$7), the Party Joy series squarely targeted the allowances of its primary school demographic.

Party Joy games had a prominent logo mark that echoed the red, tripartite brand of its Joy Family sibling. But instead of cards, the logo resembled a folded map, referencing the play board tucked within its diminutive sliding box. Beneath the katakana パーティジョイ Party Joy, Bandai included a small yellow circle with the series number, a sly marketing tactic that certainly compelled more obsessive compulsive children (and certain older game scholars) to collect as many as they could.

But the Party Joy games’ most striking material feature was their size. Each game measured 8.5 x 6.2 x 1 in. (22 x 15.5 x 2.8 cm), only slightly smaller than B5 paper size. For a Japanese child in the 80s, this would have traveled conveniently alongside both the pervasive, B5-sized Japonica learning books (ジャポニカ学習帳) or the latest manga digest. Like the sugoroku of decades past, Party Joy were designed for simplicity and travel. And as commodities, they were designed for collection, display, and licensing appeal.

Unlike Joy Family’s traditional lidded box design, Party Joy games had an inner tray that slid out from the outer box’s right edge. The tray was initially printed cardboard that duplicated the box artwork in monotone and had a small adhesive pull tab to help grasp the inner box. In 1985, Bandai replaced the cardboard with molded plastic trays in pastel hues of green, blue, yellow, and (for at least one game) pink. The trays included a short folding flap on the right side that clicked into place when closed. At the top of this flap was an embossed Party Joy logo, and at its center, replacing the green pull tab, was a ridged thumb grip. The tray’s bottom had six recessed posts, four at the corners and two at the center of each longer side, as well as a small center hole. This clever design feature allowed the tray to serve as a platform for game accessories. The same plastic standees that held players’ cardboard pawns would fit into the recessed holes in order to hold, for example, cardboard walls for a 3D diorama. Similarly, the center hole could be used to fix a through-hole spinner mechanism, converting an unused storage tray into an active game component.

The Party Joy box became the key affordance for Bandai’s game designers. All components necessary for play, from the rule book to the game board, had to fit within the small sliding compartment. As the logo indicated, double-sided game boards were printed on thick card stock that could be folded or cut into, say, fourths or sixths, and stored within the tray. To further save space and manufacturing costs, playing cards were printed on perforated sheets that players would separate during setup. These printed sheets allowed Bandai to deviate from standard playing card size, so a single game could have myriad card types and shapes—standard, square, miniature, and more. Other standardized elements would appear across multiple games (and even non-Bandai games), including four plastic standees in primary colors (yellow, blue, red, green) and a miniature six-sided die with a large red circle for the one face, presumably evoking the Japanese flag.

Most Party Joy games used sugoroku-style mechanics. With few exceptions, either dice rolls or spinners drove player movement, while cards and other accessories factored in additional chance or strategy mechanics. Owing to the series’ target audience, Bandai’s design focus was on simple setup and play, eye-catching artwork, and novel, toy-like constructions. In survey postcards included in many Party Joy games, Bandai asked, “What kind of game would you like to see in the future?” The answer choices included, “more three-dimensional,” “quick play,” “ more thrilling game subjects,” “fun board designs,” and “nice components.”

While Bandai’s idea of “thrilling subjects” predictably included licensed properties, the range of genres the series covered in 135 games is impressive, spanning horror, sports, travel, adventure, exploration, cooking, fantasy, humor, racing, and more. At the series’ peak, Bandai was releasing a game or more per month, so their stable of designers were expected to churn out game prototypes at a remarkable pace. In a 2015 interview, game designer Ikuo Nomura explains that he was among several outsourced contractors that Bandai hired to create their Joy-affiliated games. Due to limitations on copyright terms, game production had a short life span. No matter how well a particular game sold, after six months, it was taken out of production. As a result, Nomura explains, he had to focus on game designs that, inspired by sugoroku, did not require extensive rules to play. But conversely, speedy turnarounds allowed the designers to experiment with mechanics and styles, because failures and successes alike would be short-lived.

Nomura describes Party Joy’s material limitations as a kind of “platform”. Since the game’s price was fixed at ¥1,000, he explains, this set a hard limit on how much paper he could use or how many components he could include. Nomura tended to use spinners rather than dice, for example, because they were cheaper, and he could weight the random results easier. And no matter how clever a game component might be, it had to fit within the plastic tray. Ultimately, these same constraints would lead to the series’ demise—at ¥1,000, it was difficult to design board games with enough strategic interest to encourage long-term play. Such limitations would be a significant handicap as videogames began to attract young peoples’ time and money.

Joy Family vs. Family Computer

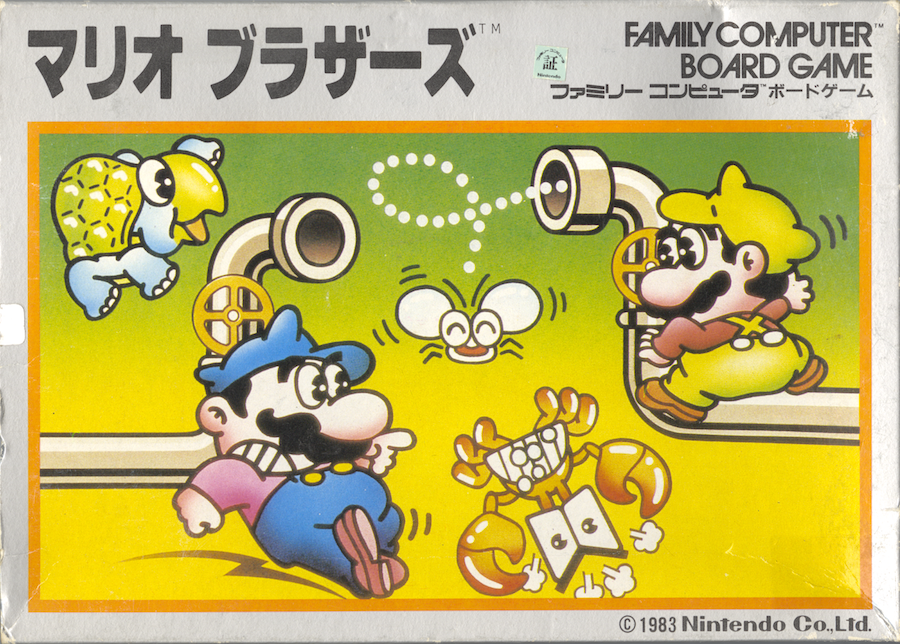

Bandai’s Party Joy and Nintendo’s Family Computer both arrived in 1983, and the impact of the latter would eventually spell defeat for the former. Videogames certainly didn’t catch Bandai by surprise. They’d been trying to make the new medium a viable business since its inception, dipping into consoles, electronic handhelds, and third-party development. In fact, the Joy Family series’ Crazy Climber, released in 1981, was among the first, if not the first, licensed board game adaptation of a popular arcade game. But it wasn’t until the Famicom gained momentum that Bandai’s videogame licensing kicked into high gear.

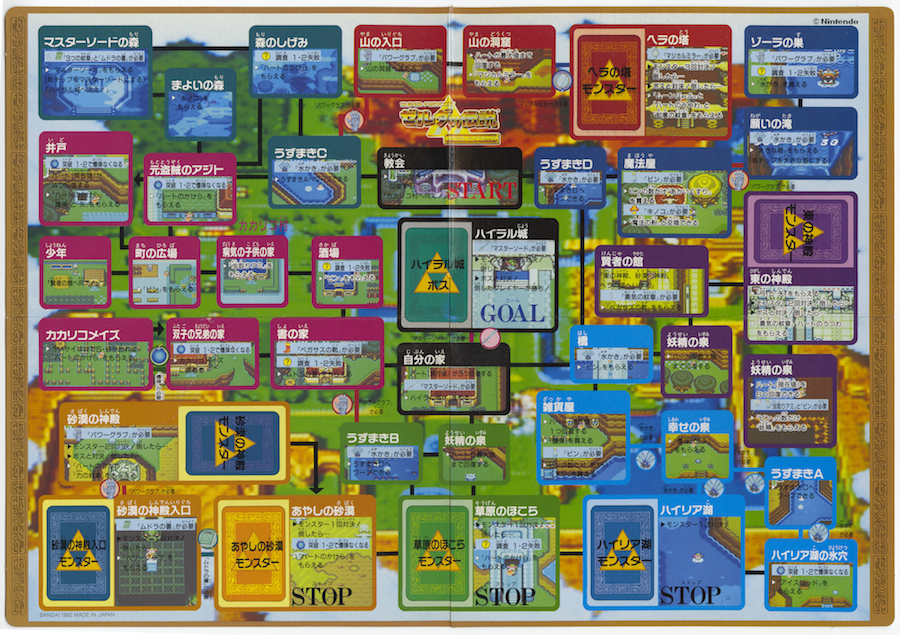

Nintendo’s Family Computer initially didn’t set the homeland on fire, but by 1985, buoyed by the breakout phenomenon of Super Mario Bros., the landscape of Japanese videogames was irrevocably changed. Japan already had a vibrant arcade culture, but Famicom brought the arcade home for millions of eager players. Bandai showed no hesitation licensing this new trend. Party Joy #51, スーパーマリオブラザーズ Super Mario Bros., was released the same year as the Famicom cartridge and featured the same cover artwork. Propped side-by-side, it’s remarkable how the Party Joy game looks like a deluxe version of the Famicom game, and Bandai certainly didn’t miss this comparison either. In the next year, Party Joy releases were almost exclusively dedicated to videogame licenses, including ツインビーゲーム TwinBee (#56), ゲゲゲの鬼太郎 妖怪大魔境 aka Ninja Kid (#58), グラディウス Gradius (#60), ゼルダの伝説ゲーム aka The Legend of Zelda (#61), マイティボンジャックゲーム Mighty Bomb Jack (#62), 謎の村雨城ゲーム aka The Mysterious Castle Murasame (#63), and 謎の村雨城ゲーム aka Commando (#64). On the Joy Family side, there were adaptations of Super Mario Bros. (in a DX, or deluxe, version), Super Mario Bros. 2, and 魔界村 aka Ghosts ‘n Goblins. Whether these adaptions proved more or less popular than previous board games is unknown, but after Bandai’s initial licensing barrage, their videogame licenses precipitously decreased.

Bandai’s competitors tried to hitch their wagon to videogames as well. Takahashi released a six-part Family Computer Board Game series clad in silver boxes that were nearly indistinguishable from Famicom boxes apart from their size, which was identical to Party Joy boxes. Namco decided to release board game versions of their own properties in two short-lived runs. Their Fantasy Board Game series released conversions of Tower of Druaga, Dragon Buster, and Pac-Land in 1986, followed by the Namcot Handy Board Game series, comprising only two games: Valkyrie’s Adventure and Super Xevious. (In English, “Handy Board” reads like an awkward linguistic construction for “portability,” but in Japanese, the name was strategic. Note that the characters for ハンディ “handy,” at a glance, are strikingly similar to the パーティ “party” in Party Joy, plus and minus a few diacritics.) A few years later, Enix would adapt their Dragon Quest franchise to multiple board and card games (which continue today), but beyond a few one-offs, no other company besides Bandai would attempt such a sustained videogame licensing schedule.

One recent account of Japanese board game history (日本懐かしボードゲーム大全) claims that the rise of videogame adaptations demonstrates how the Famicom bolstered rather than damaged the 80s board game market. While key licenses may have driven some videogame players to board game adaptations, the market crossover must have had a significant impact on Bandai’s bottom line. Time spent playing videogames was time not spent playing board games. And despite the price differential between a Party Joy box and a Famicom cassette, millions of consumers clearly didn’t mind paying 3x or 4x more for the latest electronic diversion. Bandai obviously didn’t abandon the board game business post-1986, but Joy Family’s and Party Joy’s balance of original versus licensed games clearly swung toward the latter, signaling the need to tie their series to established media properties. But even Gundam couldn’t keep Joy afloat—by 1990, all of Bandai’s board game series were sputtering to a finish. Releases became more staggered (there were only three Party Joy games in ’90, including Super Mario World), licenses were less diverse (nearly every property was owned by Toei Animation), and sequels were prevalent. Consumer entertainment dollars were clearly shifting to videogames.

One of Bandai’s most interesting last-ditch efforts to revive the line was the spin-off パーティジョイ指南役 Party Joy Instructor series, which began in 1991. The games were all licensed Super Famicom adaptations (including Nintendo’s ゼルダの伝説・神々のトライフォース aka The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Capcom’s Rockman 4) sheathed in silver boxes featuring a prominent line drawing of a SFC game cartridge. The “Instructor” gimmick was a hybrid board game/strategy guide. Original artwork was interspersed with in-game screen captures, and portions of the instruction manual and game board were dedicated to strategies for the titular videogame. Ostensibly, while you were playing the board game, you were learning skills that would transfer to the console. Whether the Instructor series served its intended purpose is unclear, but judging by the series’ quick demise after seven games (and their relative scarcity today), videogame players weren’t biting.

Bandai’s decade-long run of board game releases are remarkable not only for their sheer quantity, but for their breadth of genres, their shrewd attention to construction and design, and their willingness to experiment within proscribed constraints. It’s easy to dismiss these games as children’s fare or simplistic spin-and-move games, but there’s a rich vein of Japanese culture hiding beneath these mere sugoroku. Just as picture sugoroku superseded board sugoroku as players’ tastes changed, a significant sea change in entertainment consumption re-shaped board games’ design parameters in 1980s Japan. While prior media like television, manga, and anime had provided lucrative fodder for board game design in prior decades, videogames proved to be a competitor hewn too close to board games’ procedural core. Bandai tried both cooption and conciliation as strategies to compete with the new medium, but concession proved to be the only viable course. And while they ultimately didn’t survive videogames’ market incursion, Bandai’s board game adaptations are a significant, yet still largely overlooked, branch of (video)game history.