Rule Horizons

The Obstruction

In a recent episode of the Giant Bomb podcast, co-host Drew Scanlon brought up a rather bizarre play that happened in Game 3 of the World Series. The game ended with a Cardinals win due to an obstruction call, a rare circumstance that results from a defensive player obstructing a base runner’s path. Though I love and play sports, I don’t actively follow any these days (no cable TV), so I had to search online to find the story.

According to CBS Sports writer Mike Axisa, ‘Third base umpire Jim Joyce called obstruction on Red Sox third baseman Will Middlebrooks, who interfered with Allen Craig when he broke home on Jarrod Saltalamacchia’s poor throw into left field. It’s the right call. You don’t see it very often, but it’s the right call.’ You can watch the play in question at the link above and read Axisa’s comprehensive explanation of why the call was ‘by the book.’ He cites the lengthy description from Rule 7.06, which can be found in the 2013 Edition of the Official Baseball Rules. Specifically, page 64. Of a 125-page rulebook.

I played hours and hours of baseball as a kid, but I’ve never read the rules. They were taught to me by others during play. And despite this vernacular knowledge, I can follow a baseball game perfectly fine. My wife and I attend AA baseball games in our hometown all the time. I even know what a balk is. But I’d bet that very few fans or even players have read the Official Baseball Rules. It is likely the exclusive purview of referees and few others.

I love Axisa’s closing sentences: ‘What a crazy, crazy way to end a World Series game. Baseball is so much fun.’ Despite the need to reproduce a thick block of rules-text to explain to his readers why this call was made, and despite this arcane ruling ruining the day of thousands of Red Sox fans, there was no apparent ire. Rather, this call reminded Axisa of baseball’s unseen complexity, its hidden nuance.

Scanlon and co-host Jeff Gerstmann had the same reaction:

Drew: I love that so much weird stuff can happen in baseball. It’s one of those games that has so many rules, but stuff still happens that’s weird.

Jeff: Exactly. And they’ve got rules seemingly for all of it, no matter how obscure some of that stuff gets. Yeah, a lot of the rules for stuff like that, and interference, and all that, is strange.

These rules are strange because they’re designed to account for edge cases, not conventional play. Millions of children and adults watch and play baseball, but I’d guess few could recognize the obstruction violation. Even Fox’s announcers took a long pause after the home plate referee called Craig safe when he’d clearly been tagged. The players and coaches looked confused. Likewise, Fox followed the call with two minutes of replay footage from all possible angles. It was a ‘high-level’ rule reserved for an exceptional occasion, and it brought the game to an exhilarating conclusion.

Consider the opposite end of the spectrum. Baseball’s ‘low-level’ rules are simple. Two teams trade off batting and fielding. The fielding team has a pitcher who tosses the ball to the opposing team’s batter. The batter tries to strike the ball as far as possible toward a region of the playing field unoccupied by the opposing team. The batter only gets a few tries to do so, but the pitcher must throw ‘fair’ pitches. If the batter gets a hit, they must run a series of bases without getting tagged out. If they complete the circuit, they score a run. After a set number of outs, the teams switch roles. Highest score wins.

This summary is enough to get a pickup game going. The rest you can learn by playing. You may have learned with even less instruction: ‘Here’s the bat. Try to hit the ball. If you do, run to that base.’ Broken into its constituent play elements—tag, catch, running, hitting—baseball is even simpler.

This simplicity is part of baseball’s enduring appeal. Even though most of us will never ascend to professional player status, baseball’s fundamental ruleset is straightforward enough for most people to understand and enjoy. The rules, and players’ mastery of the rules, take on an aesthetic dimension that is satisfactory enough to observe in their own right. One can enjoy baseball without ever having actually played the game.

Rule Horizons

Baseball, and other games of its kind, exhibit what I call ‘rule horizons,’ expanding layers of complexity that radiate from a central core ruleset. Crossing each horizon offers a new benchmark of excellence and mastery for those players (or spectators) who choose to pursue it. But crossing horizons is never a necessity for play.

I’ve thought about this concept a lot recently because I’ve spent more hours watching videogames in the past year than playing them. Part of this is a function of priorities—I often don’t have the time or money or proper platform to play all of the videogames I’d like to, but as a scholar interested in the medium, I like to try and stay abreast of what people are playing. Watching YouTube or Twitch also fits into small cracks of time that I normally can’t spend playing videogames: eating breakfast, cooking dinner, getting ready for bed. Finally, I find the vibrant communities that surround Let’s Plays, Twitch streaming, Quick Looks, and the like sociologically fascinating. It turns out that *lots* of people enjoy watching other people play videogames, a fact that scholars and pundits who beat the drum of ‘interactivity’ as the medium’s primary strength should take note of. (Not to mention the questions of class privilege that arise from a) observing a community of typically young white males who b) have the leisure time to devote to playing videogames for entertainment and/or profit.)

One of my favorite observation subjects is Spelunky, the ‘rogue-like’ platformer that draws influence from a bizarre range of sources: Super Mario Bros., its namesake NES game Spelunker, Rogue, the Indiana Jones films, ancient Aztec culture, Indo-European mythology, Judeo-Christian symbolism, the horror genre, and more. It’s a weird game, but I also think it’s one of the most thoughtfully-designed, sophisticated, and important games in videogame history. It’s in the same league as Super Mario Bros.—or baseball.

I’ve spent about a hundred hours playing Spelunky and likely three times as many hours watching others play (as horrifying as it is to acknowledge that fact). It is also one of the only games I’ve ever watched someone play to completion before I tried to play myself. And the reason I think I continue to find myself so enthralled by Spelunky is the same reason Drew Scanlon and Mike Axisa find baseball so weird and wonderful—its rule horizons.

Into the Depths

Spelunky’s first horizon is the same as Super Mario Bros. and countless other platformers: run, jump, avoid enemies, surmount obstacles, and get to the end of the stage. But Spelunky’s difficulty is more taut and steeply-scaled than its forebear. Most beginners will die often, with cruelty, and with fairly little understanding of why they died.

Spelunky is divided into four areas—mines, jungle, ice caves, temple—each of which has four levels and its own unique ecology of traps, terrain, and enemies. True to its name, Spelunky eschews the left-to-right convention of its platforming brethren in favor of descent. Though you often have to shuttle left and right to find a path, your primary vector is down.

The mines are paradoxically Spelunky’s most brutal area. Each time you start a game, you start fresh, with no items and only the complimentary stock of four hearts (your lifeblood), four ropes, four bombs, and a whip. Grab a cape on your last playthrough? Sorry, but you forfeited it when you died. This mechanic, along with Spelunky’s procedurally-generated level layouts, is the reason the game gets its ‘rogue-like’ descriptor. Every playthrough is a new beginning, for better or worse. There are no extra lives. (Yet.)

So Spelunky’s first horizon is survival. You will be stuck in the mines for a long time trying to cobble together enough resources to live until the next level. You’ll use bombs and ropes carelessly, because your chances of survival are unlikely. Smoke ’em while you got ’em. When the ‘dark’ levels appear—reducing your ambient light to a torch’s weak halo—you’ll despair. Each new enemy and item is a puzzle. What triggers the bat’s flight? How do I dispatch the giant spider? What happens when I approach the pile of bones? What happens when I snatch the golden idol head? Why are there jewels embedded in rock?

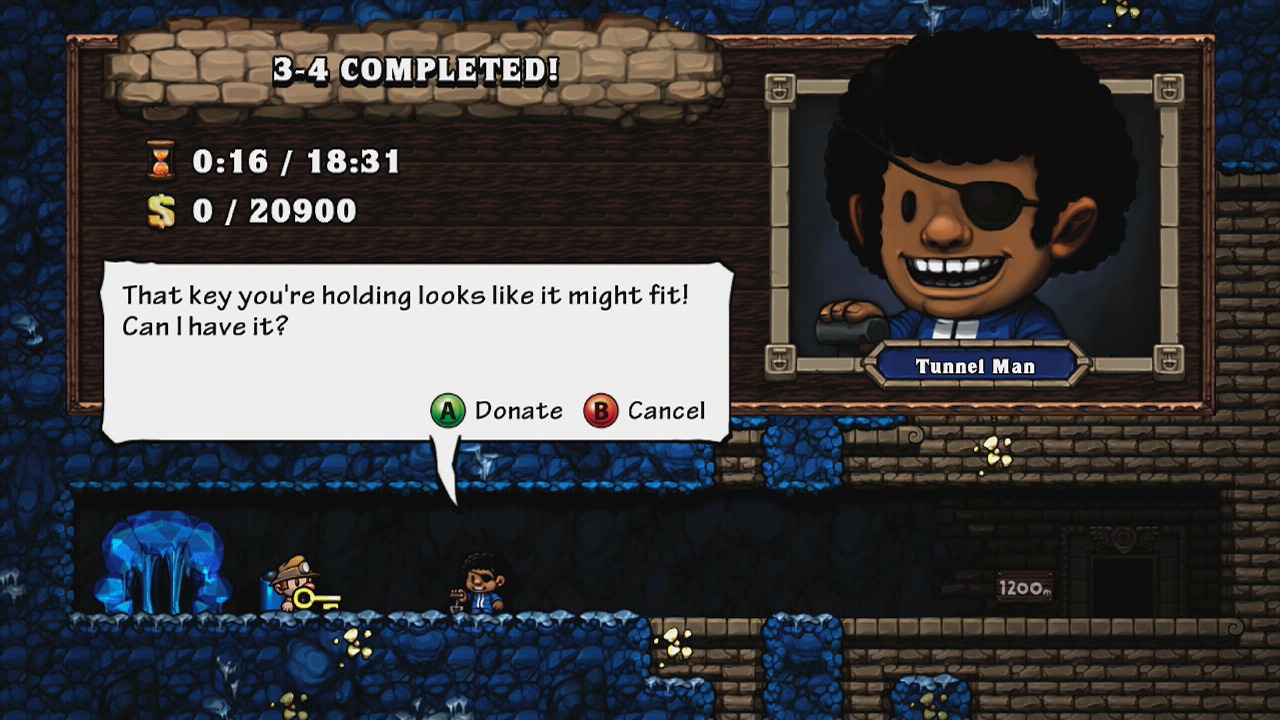

Slowly, with practice and experience, the rules expand to a new horizon. If you make it through the mines, you encounter the Tunnel Man. The Tunnel Man lives in Spelunky’s interstitial scenes, offering to dig a series of shortcuts if you’ll trade him your precious resources. It’s a devil’s bargain—the last thing you’ll likely want to relinquish when you first conquer the mines is a bomb, or a rope, or your hard-earned $10,000. But the promise of skipping the mines indefinitely (the only persistent state the game offers) is alluring. And each time you fulfill the Tunnel Man’s request, his demands escalate, culminating in two rare items: the shotgun (to unlock the ice caves shortcut) and the mine key (to unlock the temple shortcut).

Both requests are gentle hints at new horizons.

One can acquire the shotgun legitimately by purchasing it from a shopkeeper, but it’s relatively expensive in the early game. It’s also randomly available in crates or procured from a grave in the ‘dead are restless’ levels. But most importantly, it’s wielded by the shopkeeper.

In the early game, shopkeepers are your allies. They provide access to random and sometimes rare items that can help you survive. But once you discover, either by accident or experimentation, that you can kill them and loot their supplies, they become one of the game’s most dangerous and persistent enemies. Once you violate the shopkeepers’ trust, it’s almost impossible to mollify them. They prowl their shops, vaults, and the exits with tireless vigilance. But killing shopkeepers is a necessity for later rule horizons. One cannot maximize one’s score without stealing items, collecting shopkeeper gold, and excavating their vaults.

The key is less risky to obtain. It’s always stashed in a mine level—sometimes conspicuously, sometimes not—along with its complementary locked chest. Unlocking the chest nets you the Udjat Eye, whose immediate benefit is revealing every level’s hidden treasures. Many of the jewels and items dispersed throughout the level’s earthy crust are invisible. More importantly, the Eye is the first in a long series of steps necessary to unlock the game’s high-level horizon: the hidden fifth level, Hell. However, to return the key to the Tunnel Man requires that you forgo the Udjat Eye and convey the item through several intervening levels, from the mines to the end of the ice caves. To do so is particularly difficult because you can only hold one item at a time. In other words, if you want to pick up pots, weapons, enemies, or anything else, you must ‘juggle’ them with the key.

Transporting the key is one of the early game’s most difficult tasks, but it opens the final shortcut to the mines and subsequently a direct route to Spelunky’s ‘final’ boss, Olmec. But this also introduces a new horizon. Circumventing the opening three areas raises the temple area’s difficulty. If you arrive there during normal play, you’ll hopefully be outfitted with several items, more health, and/or an increased stock of bombs and ropes. If you use the shortcut, you start with the same bare supply list that you begin with in the mines. The shortcut is less of a winning strategy than a quick means to practice the temple prior to reaching it ‘legitimately.’

Assuming you reach and defeat Olmec, you have ‘won’ Spelunky. It’s a difficult, worthwhile accomplishment in its own right. But it’s also the equivalent of the baseball pickup game. You’ve learned the basic rules—now it’s time to move up to the Little Leagues.

The Spelunky World Series

Most players’ next immediate goal is to find, reach, and conquer Hell. The rules horizon necessary to do so is one of Spelunky’s most difficult challenges. One must: find the mine key, unlock the chest, obtain the Eye, use it to find the hidden Black Market in the jungle, buy the ankh item therein for the sizable sum of $50,000, spot the Moai in the ice caves, die in that level so you can resurrect inside the Moai and collect the Hedjet, defeat Anubis and obtain his scepter in the temple, use the scepter to unlock the golden door and access the City of Gold, snatch the Book of the Dead, use the book to spot and access the door to Hell in Olmec’s room, then maneuver Olmec to smash a path to the door and ride his head down so you may use it as a platform to enter said door. Only then may you fight your way through Hell, one of the hardest areas in the game. Congratulations—you’ve pitched a perfect game.

The fascinating thing about Spelunky is that its rule horizons don’t stop there. While defeating Hell is a massive accomplishment, it is not the game’s pinnacle achievement. When Hell becomes the norm, a new horizon comes into view: the high score. The million-plus run is the purview of Spelunky’s elite players. While you can achieve multiple hundreds of thousands playing ‘safe,’ i.e., not killing shopkeepers, only those who follow the rogue’s path and plunder their vaults have any chance of topping the high-score list. Furthermore, one of the game’s punitive mechanics, the unstoppable ghost that appears if you dawdle too long in a given level, transforms from a frightful menace to a treasure-making machine. When the ghost’s body passes over jewels, they change to diamonds, multiplying their value. ‘Ghosting’ vaults and errant jewels is the key to the highest scores. (And as you can see, new rule horizons also demand ad hoc lingo and insider knowledge to describe their dimensions.)

At the furthest rule horizons, Spelunky is a fundamentally different game. Yes, the base mechanics are still the same—run, jump, avoid enemies—but the aesthetics have shifted. And it’s not a simple repetition of the adage, ‘Easy to learn, hard to master.’ There’s something else at work. Rules that applied in early stages of play now no longer apply. High-level players never use Tunnel Man’s shortcuts; doing so forfeits the chance to go to Hell and maximize one’s score. The ghost, which early on had to be avoided at all costs, is now a necessary companion. Shopkeepers should be slain at one’s earliest opportunity. The World Series of Spelunky is not the same as playground ball.

(And also note that rules horizons apply in both directions. Calling obstruction in a pickup game demonstrates a misunderstanding of one’s current play landscape—and makes you sound like an asshole.)

Spelunky has so many concentric, overlapping, and/or juxtaposed rules horizons that it is impossible to encompass its landscape of play. Some play the game as fast as possible. Others play without collecting gold. Others are poking at its procedural limits. Others are attempting Spelunky’s version of the obstruction—carrying the eggplant, the game’s most fragile and useless item, to Hell and flinging it at the game’s final boss.

And while thousands play, thousands more watch. But why?

Because just as one cannot exhaust baseball or football or poker or chess or Dungeons & Dragons, one cannot fully plumb Spelunky’s depths.