The Long Walk

Silent Hill 2, horror, and duration

Our gaming priorities change as we get older. In my late teens, when I purchased my first console with my own money (a Sony PlayStation), the prospect of 50+ hour roleplaying games seemed like a sound fiscal investment. I could only afford two or three games a year, so they had to last. Of course, gameplay length comes in different forms. In Final Fantasy VII, you spend a lot of time ‘outside’ of the game’s narrative structure—playing mini-games, exploring, grinding experience, and so on. In Gran Turismo, your hours come from perfecting racing lines, tuning, and earning new cars and licenses. The range of courses is limited, but replay value comes from practice and variation. In Tekken 3, the game’s life extends through multiplayer. The endless iterations of two-player combat mine dozens of hours of gameplay from a small pool of characters and arenas.

Now in my thirties, I shudder at the prospect of mammoth time sinks. It is not strictly the overall time commitment, but individual session lengths. I’ve now sunk over forty hours into The Binding of Isaac, but most of that time has been broken into thirty or forty-five minute chunks spread across several months. I probably have several hours of Tiny Wings hill-gliding under my belt, but individual rounds only take a few minutes at most. With pressing commitments to family, work, or school, such games are more manageable to fit into adult schedules.

Unfortunately, game journalism has not divested itself fully of the hours = value metric for granting that extra 0.2 of FUN FACTOR on the review scale. Limbo was criticized by some as too short. I played through in roughly three hours and thought it could have been shorter. Not because I disliked the game, but because I thought it said what it needed to say in the first hour or two.

Cinema, that longstanding object of videogame affection, never suffers critical ire based on brevity. If anything, it’s the opposite. Films that push the two hour mark better be about hobbits or wizard schools, otherwise YOU ARE TESTING MY PATIENCE. A forty-hour film is a gallery piece or an outlandish experiment, not a work of mainstream cinema. Yet ‘cinematic’ games like Uncharted never aspire to the brevity of their film inspirations. Or perhaps in a perverse way they want to equal the length of all of their inspirations in a single package.

Games largely waste their durational privileges. Fifteen hours into Assassin’s Creed, what are you doing? Likely the same things you were doing in hours seven and three: stabbing, climbing, skulking, blending, and tossing shekels to the groveling 99%. Grand Theft Auto? The same. Final Fantasy XIII? Oh God. In the end, a game’s worth often boils down to whether its core mechanics can bear the strain of several dozen hours. In the absence of sturdy mechanics, hopefully there’s an enjoyable world to explore. Thrilling locales can compensate for faulty gameplay. An uncommon few nail both.

The shame is that duration is rarely explored in its own right. Developers have an audience of millions already accustomed to a deep, concentrated temporal investment in their medium. But they routinely use that resource for value padding. ‘If the player has fun using the cool new chain blade weapon, why not give them five more hours to do so?!’ Few videogames value our time; fewer still aim to examine it with aesthetic purpose.

Cinema has understood duration as a tool for tension and release for decades. Find an evening to watch Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker and tell me you don’t feel a palpable discomfort at the long, unbroken shots that threaten to hold your gaze to the point of exhaustion. Tarkovsky actively worked against the conventions of film, subverting the desire to propel narrative along via montage, long held by film theorists to be the lifeblood of the cinematic form. What happens when we force the viewer to linger on an image for minutes without cutting? With pronounced duration, each cut serves as a reprieve to the taut stillness of the preceding image.

The famous opening shot of Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó lingers for over seven minutes, with no cuts, on a herd of cattle. You feel as though you’re stuck, along with the camera and cows, in the thick troughs of shit and mud. In today’s era of rapid cuts—the ‘MTV school’ of montage—Tarr’s scenes are hard to watch. They can have a brooding, meditative effect, but they require a kind of physiological submission to a different experience of cinematic time. Not time, but duration—a subjective experience of objective time.

Good horror plays with duration. The camera that tracks through a darkened hall with unwavering slowness helps build suspense and anticipation. At its culmination, the tension breaks; either the monster or the unwitting friend appears from the shadows, accompanied by a startling audio cue. In either case, the viewer has release. But film has its limits: shots can only last so long, horror can only grow so taut.

Videogames do not share cinema’s temporal shackles. The medium’s conventions allow for sustained, unbroken ‘shots,’ often with the camera in a fixed position. Players are accustomed to visual fixity.

The best horror games exploit those conventions. Silent Hill 2 is a master of the form. As the series expands into multiple sequels, comics, and, yes, films, critics wonder why Konami cannot recapture the magnificent dread of the PlayStation 2 debut. Yes, SH2 openly cribs from filmic precedents like Jacob’s Ladder and even the weird macabre body horror of painter Francis Bacon or the obscene mannequin photography of Hans Bellmer. And yes, the game relies on psychological horror more than jump scares or horror movie cliches. But numerous failed attempts to mimic SH2’s visual tropes in subsequent games and movies have led to unanimous critical disappointment. Why? The developers lack SH2’s exquisite recognition of temporal horror.

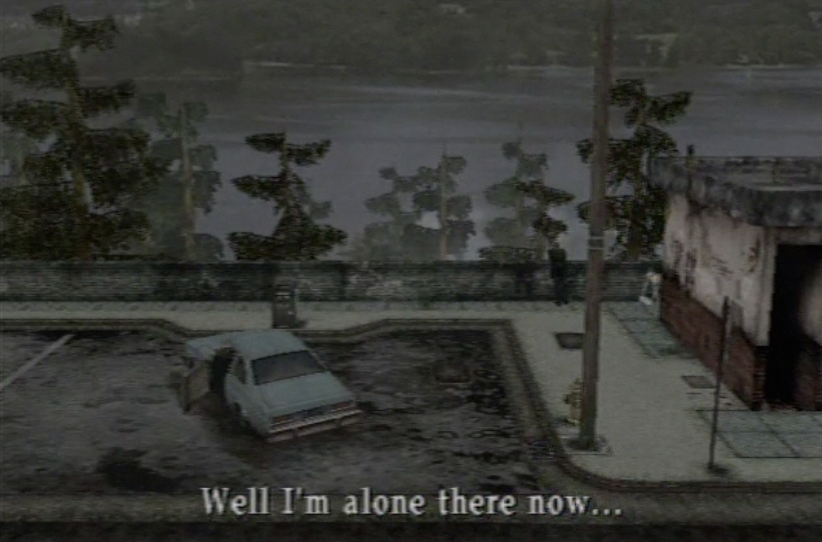

Consider the game’s opening scene: James Sunderland has received a letter from his wife, informing him that she awaits their reunion at their ‘special place’ in Silent Hill. She has been dead three years. James stares into the mirror of a rundown rest stop bathroom and runs his hand down his face as if to question his own corporeality. Is he dreaming? Can the letter be real? James is compelled to find the answer.

The road to Silent Hill is blocked, so James must abandon his car and proceed along a snaking forest trail that follows the shoreline of Toluca Lake.

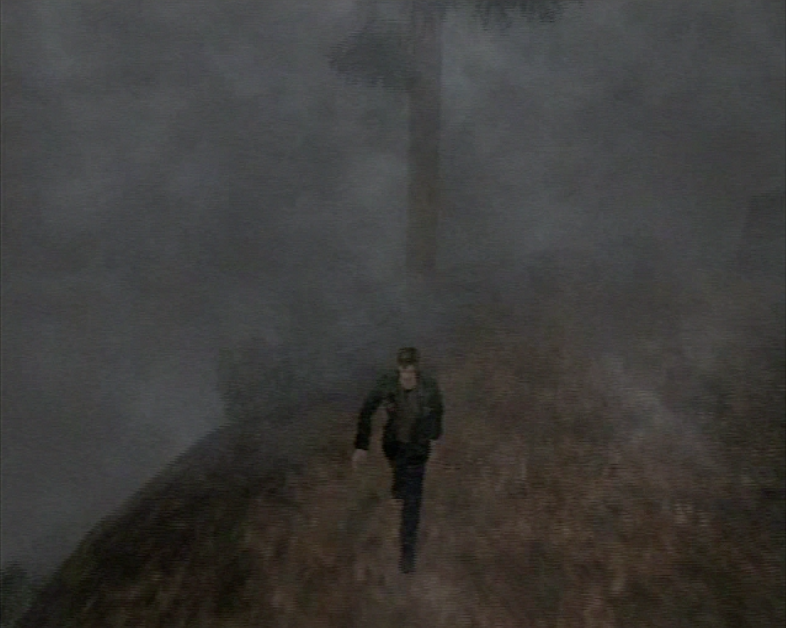

The forest path is a horrific place, shrouded in the palpable volumetric fog (a series trademark) coursing incessantly through Silent Hill’s environment. There are no enemies, no combat, no encounters. There is barely a there there—the grey mists swallow James, the flat textured terrain, and the polygonal trees.

In short, nothing eventful happens in the forest. There is just the long walk.

It is hard to convey the terror of travelling the forest path secondhand. Even now, as I play it again after an eight hiatus, the tension is diffused; I know that no harm awaits James. (And now I’ve likely spoiled your own experience.) But the first time I played, I was unnerved. The blinding grey demanded that I walk slowly in case I was attacked, but the looped drone of the soundtrack and the churning white noise of Toluca’s spray exerted a tangible claustrophobia. Two other intermittent audio cues punctuated the background din, both indiscernible clatters that evoked the improbable grinding of metal, bone, leaves, and sinew. As you walk or run, you also hear James’ footfall, whose uniform digital crunch rings hollow against the concerted moans of the lake and the throbbing soundtrack.

I admit that I ran my first time. Potential enemies be damned, I had to get out of the forest.

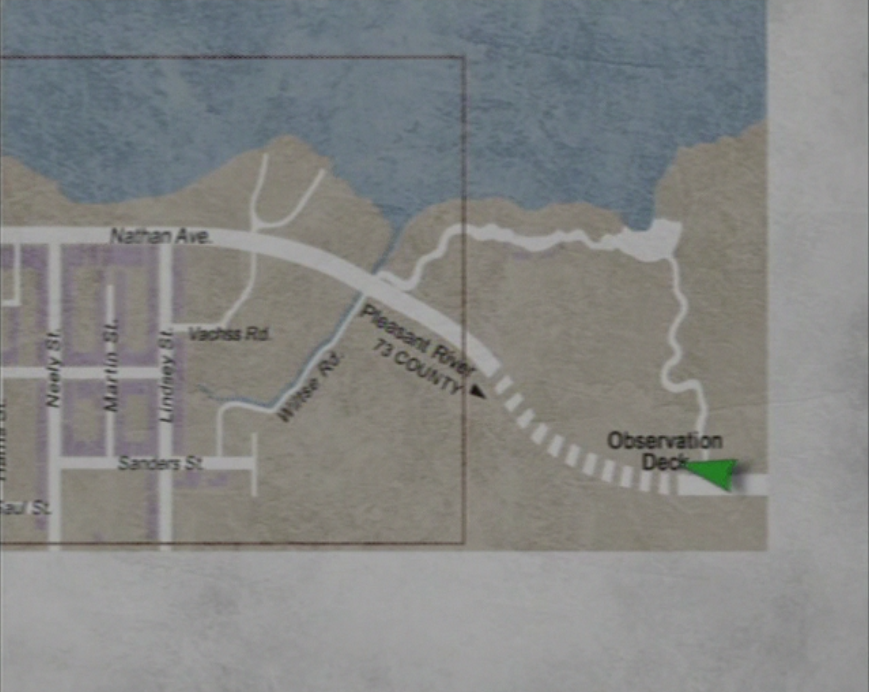

At a walk, the whole sequence takes two or three minutes. As you progress, James passes through five camera angles, each used to great effect. The first faces James directly, at a slightly elevated height. This is an unconventional perspective in videogames, typically reserved for chase scenes, when the player is meant to avoid a threat pursuing her character from behind.

Here, there is no pursuer. Instead, you are compelled to walk toward the unknown, while the sole safety of your starting locations recedes into fog. When James turns the first bend, the camera draws uncomfortably close to his position, effectively eliminating any view of the path ahead. Like the letter, the camera is leading James toward Silent Hill.

The first cut moves the camera to James’ right side, at a distance, and frequently obscured by trees and fog. The camera is predatory; it surveils James’ movements from its position above the lake.

The second cut moves the camera behind James, in a more traditional third-person view. The camera now follows, pursues, stalks. James (and the player) are now committed to their path toward Silent Hill, so his body is permitted to lead the camera forward.

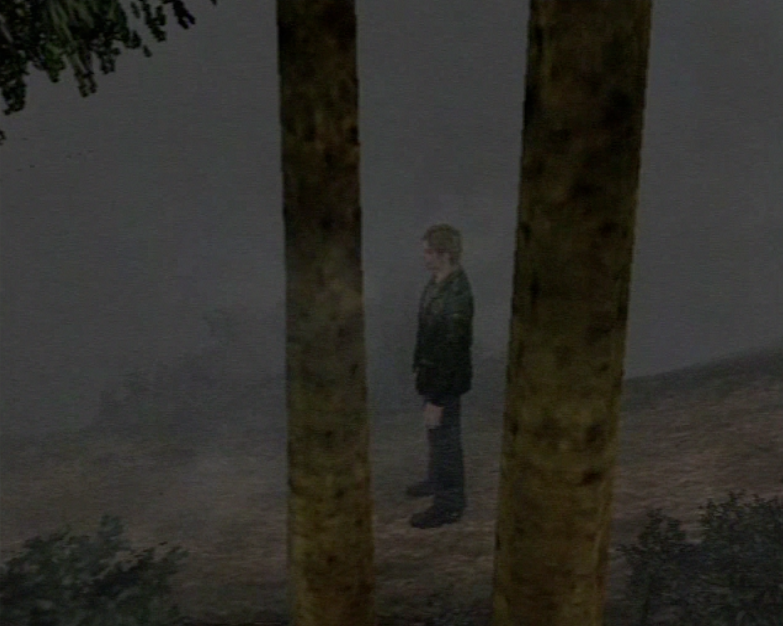

The next cut moves to James’ left side, now lurking in the forest just beyond his path. There’s a remarkable moment when James passes between two trees and we see him isolated, pinned between these dark vertical bands that foreshadow a later scene when we view James through the bars of a cell.

The final cut returns the camera to its position behind James, just before the walk ends. Soon, the first signs of human life emerge in the distance—a dry well to the right and a gate leading to a cemetery ahead. James has completed his metaphorical walk into the psychosis of Silent Hill.

The camera cuts heighten the sense of horror, but they do not function in the standard temporal mode of cinematic montage. In a film, the director controls both shot composition and the pace and rhythm of edits. In SH2, shots are deliberately framed, but the player controls montage according to spatial triggers. Beyond their linear sequence, edits fall outside of any predictable chronology. In other words, once James passed a predetermined path point, the camera switches automatically; if he retraces his steps, the previous camera angle returns. During the PSX/PS2 era, many games in the horror genre used this fixed perspective to maintain control over shot framing and presentation. But notice how the designer’s control over camera angles simultaneously sacrifices temporal control. The rhythm of edits changes according to the player’s stylistic choices. To compensate, the duration of the walk is extended. The five separate angles provide aesthetic variation, but also toy with the player’s perception that something important has changed. Why is James now viewed from the left? Is there a creature lying in wait? The beauty in these cuts is that they never resolve according to player expectations. There is no payoff, so to speak, just a lingering fermata of dread. In a film, the forest path would likely face substantial edits; it’s too long, too boring, and serves no purpose in advancing the plot. But in the hands of the player, the forest path ratchets suspense in preparation for James’ entrance to Silent Hill.

The remarkable thing about SH2 is that it manages to maintain its oppressive droning tenor for a dozen hours (7.3 out of 10!!). The tone established in that first walk persists until James’ final revelation. Monsters do come (and they’re quite wonderful), but they don’t crash through windows or spring out of closets. In most cases, Silent Hill’s creatures are best avoided. The real horror is temporal—the long walk through the forest, the descent into the prison, the meditative row across Toluca Lake. The game has many moments that wouldn’t work in cinema because they’re too protracted. But Silent Hill 2 is a game that understands horror because it understands time. Duration can be as frightening as a shambling, dismembered mannequin.