Sinter RPG: Phased Combat

Combat turns are tricky. My current tabletop group plays Dungeon Crawl Classics, which borrows the standard combat sequence from D&D and its kin. Once combat commences, players and GM roll initiative on a d20. The result of the roll (plus or minus any modifiers) determines combat turn order. Typically the GM will roll a single die for all enemy combatants (or group them according to kind) to keep things speedy. Thus, if the fighter rolls a 4, the cleric rolls a 17, and the GM rolls a 12, the cleric will go first, all monsters second, and the fighter last. This sequence repeats until combat is complete.

The immediate problem is that combat feels a bit mechanical. You take your turn, I take mine, repeat. Players who roll low remain in ‘last place’ no matter what. And most importantly, when it’s not a player’s turn, their attention tends to drift.

Some flavors of D&D permit ‘group initiative,’ where players and enemies alternate turns as a group, allowing players to strategize together and act in whatever order they deem advantageous. The drawback is that combat can swing wildly from turn to turn. A series of fortunate rolls on one side can end the fight before the other side gets a turn.

Of course, D&D is not the definitive solution to combat, merely the archetype. Over the years, many games have proposed alternate solutions to combat order. These range from ‘free-for-all’ resolution systems (where narrative takes precedence over mechanics) to regimented, second-by-second systems that require significant bookkeeping (but appeal to system-heavy types).

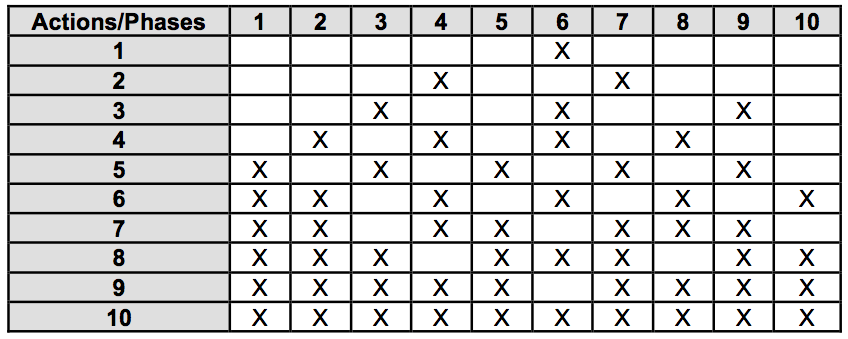

As usual, I was looking for a balance between speed and complexity. While spending a few days reviewing a number of combat turn systems, I stumbled upon the Judge Dredd RPG, published by Games Workshop in 1985. The rules include an action/phase system that I think is elegant and intuitive. Dredd represents the system in tabular format:

The rulebook describes individual actions as follows:

Depending upon your Initiative score, your Judge can perform a certain number of Actions in a particular Combat Round. To determine the maximum number of Actions your Judge can perform in a single Round, simply divide your Initiative by 10, rounding up to the nearest whole number. (Thus, an I of 9 gives 1 Action, an I of 48 gives 5 Actions, and an I of 83 gives 9 Actions.) This doesn’t just apply to Judges, but to all other characters as well. On average, a starting Judge will have either 2 or 3 Actions; with training and experience, any character can increase their Initiative scores, however, and thus increase the number of Actions they can perform.

The rulebook then elaborates on phases:

Once you have determined how many Actions your Judge can perform in a particular Combat Round, the next step is to determine when, during the Combat Round, these Actions may be performed. This is because characters with a higher number of Actions may be able to perform them before, during, and after the Actions a slower person performs.

To this end, each Combat Round is divided up into 10 Phases; you may perform actions in some of these Phases, but not in others, depending upon how fast you are. There are Active Phases, in which you may perform an Action, and Inactive Phases, in which you may not. The number of each of these two types depends on your Initiative and your Actions.

Within a particular Combat Round, all Actions occurring in the same Phase are assumed to be happening simultaneously. However, since it would be impossible for a Game Master and his players to do everything all at once, in each Phase where two or more characters are entitled to perform an Action, the character with the lowest Initiative declares the Action he is making first, and the character with the highest Initiative declares last. This represents the faster character’s ability to act swiftly on a quick appraisal of the situation. Although the Actions are declared in this order, they are actually performed simultaneously.

Contrast this to D&D’s system described above. Initiative is not rolled prior to each combat sequence; rather, initiative is a rolled attribute that may range between 22 and 40 (2d10+20). Initiative may also improve over time as the Judge advances in rank. Advancing initiative reflects the character’s improvement in skill and training over time, allowing them to act more quickly during combat.

A starting Judge can have a maximum of 4 actions per phase (I 40 / 10 = 4), meaning he or she may act in phases 2, 4, 6, and 8. From the GM’s perspective, there is minimal overhead. You keep track of the current phase and check to see which characters may act. If two characters coincide, the player with the lower initiative score announces their intended action first. Though actions in a single phase resolve simultaneously, this added ‘foresight’ grants the player with a higher initiative a slight advantage.

The main drawback I see is how Dredd handles individual actions. For instance, if my Judge wishes to pick up, aim, and fire his weapon, I must expend three Actions. Even if my Judge had the maximum starting initiative, it would take nearly an entire combat round to perform those three Actions. This is a little too slow and fiddly for my tastes, especially for a fantasy setting. Likewise, ten phases per round felt like overkill, especially if I wanted to compress multiple actions into a single phase.

Keeping with my setting’s theme of sixes (congruent with the character trades), I revised Dredd’s phase system as follows:

| ▾I / P▸ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ▲ | |||||

| 2 | ▲ | ▲ | ||||

| 3 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| 4 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ||

| 5 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |

| 6 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ |

The player’s initiative score is listed in the far-left column, while the phase numbers are listed along the top row. The reduction in phases from ten to six requires active phases to shift to the left, but I maintain the basic ‘pyramid’ shape from Dredd. The strength of that shape is that players with wildly divergent initiative scores remain reasonably balanced in combat sequence. A player with a 5 initiative, for instance, will only receive two actions prior to the first simultaneous action shared with a player with a 1 initiative. In other words, you’re not necessarily screwed if you have a low initiative—you’ve just got to make that action count.

In a later post, I’ll elaborate more on how phased combat works in practice. Unlike Dredd’s system, actions and phases may ‘shift’ left or right during combat, based on surprise, attribute modifiers, and even armor types. Combat remains dynamic, even in the absence of randomized rolls. But more on that later.