A Haze of Bizarre Angles

A Visual Essay on Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986)

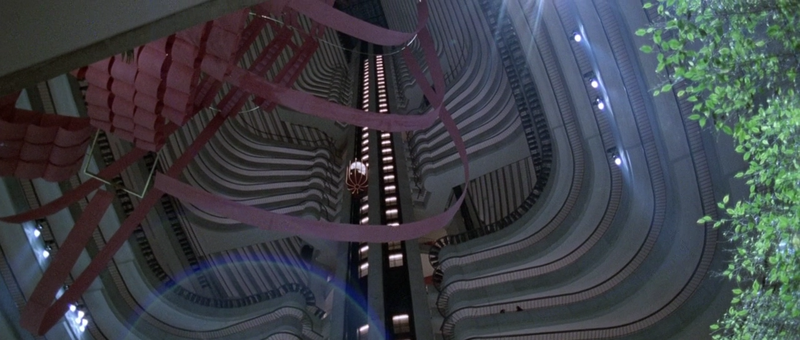

In his 1986 review of Michael Mann’s detective thriller Manhunter, Chicago Tribune critic Dave Kehr described the film as one ‘in which government offices sport $900 designer lamps, every building is a masterpiece of post-modern design and an FBI agent, a reporter for a supermarket tabloid and a slobbering psycho-killer all display exactly the same impeccable taste in expensive European casual wear.’

He continues: ‘Unfortunately, Mann doesn`t restrict himself to dressing up his actors; he dresses up his images, too, trotting out a range of camera tricks that leave the sense of every scene suspended in a haze of bizarre angles, color overlays, pretentious backlighting or unmotivated camera movements. He cuts his shots together in a way that prevents us from getting a spatial fix on the action—giving us only fragmentary glimpses of a scene, or making unmarked transitions between sequences that take place as far apart as Chicago and Washington, D.C.’

Kehr is right about Mann’s visual sensibilities—every shot is ‘dressed up’ in ways that strain the story’s ‘realism’—but calling the director’s techniques both pretentious and unmotivated is burning the critical candle at both ends. Every visual choice in Manhunter feels calculated, but not just for the purposes of vacant stylistic flourish. Mann is using color, framing, arrangement, and set decoration to tell Manhunter’s story in images as well as words.

Color and Mise-en-scène

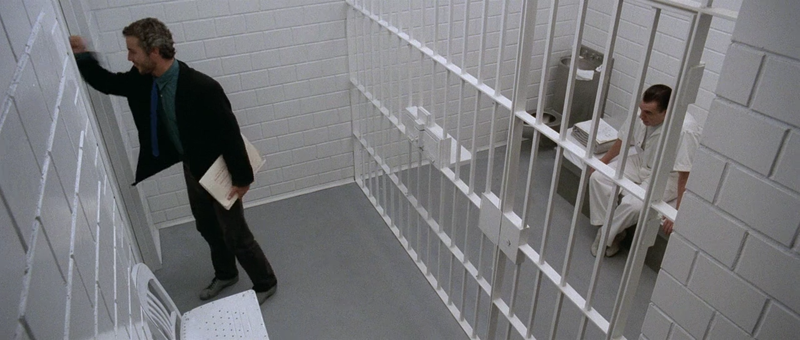

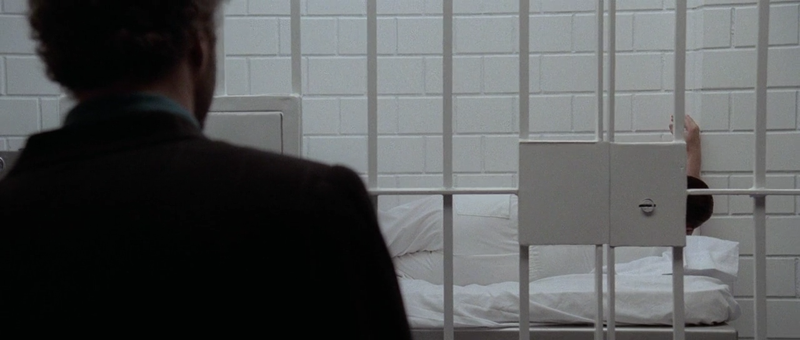

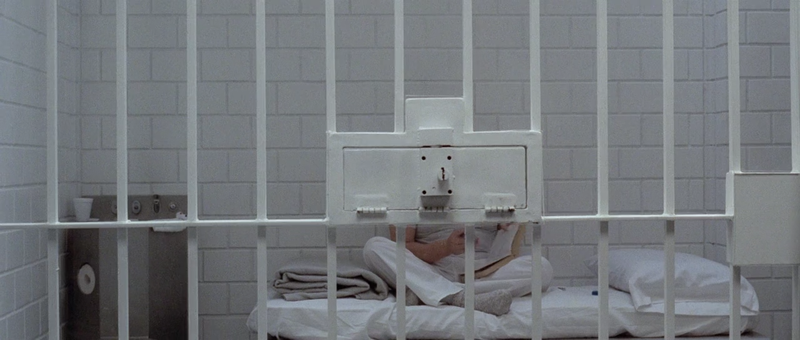

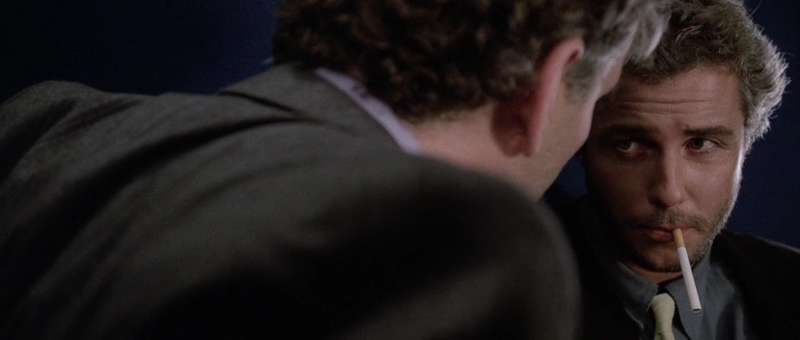

Mann arranges bodies in orderly (and illogical) distributions, frequently dominated by surrounding architecture or furniture. The camera’s viewpoint is often peculiarly low, predatory, surveilling. When the camera position changes, it’s often to convey a shift in power—when Graham interviews Lecktor for the first time, for instance, Lecktor begins to ask uncomfortable personal questions, prompting Graham to flee the interview. Lecktor gains the psychological upper hand, so the camera shifts to a raised perspective.

Also note the predominantly white palettes, typically used to convey clinical, oppressive spaces or moments of confusion and unease.

One of the most striking mise-en-scènes occurs during a staged photo op. Five bodies are arranged at varying depths, but all in focus, flattening the frame.

This scene was immediately evocative of Kurosawa’s beautiful staging in High and Low (1963), which used space as a metaphor for class hierarchy.

Similar arrangements denote distributions of power and control.

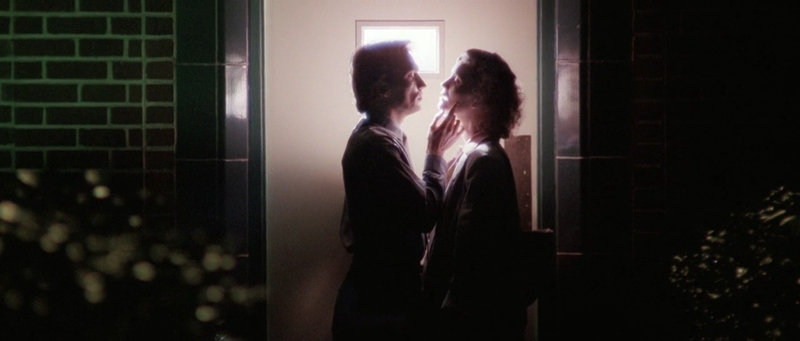

Blues/greens appear alternately as tones of solace and menace, signaling to the viewer that no space is safe. Blue is initially the color of intimacy between Graham and his family, but later that tonal indicator is subverted when the Tooth Fairy discovers where Graham lives.

Mirrors and Doubling

Mirrors are the central thematic element driving Manhunter’s story, as Will Graham discovers near the end of the film:

‘He uses the mirrors to see it happen.’

‘…because everything with you is seeing, isn’t it? Your primary sensory intake that makes your dream live is seeing. Reflections, mirrors, images…’

‘You’ve seen these films.’

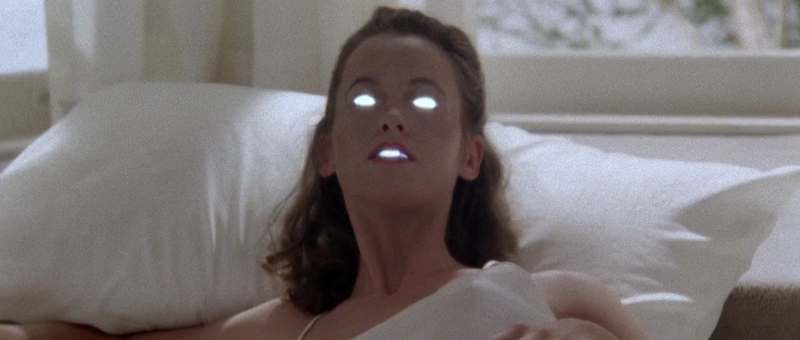

The Tooth Fairy literally destroys his victims with mirrors, then poses them afterward with mirrors in their eyes.

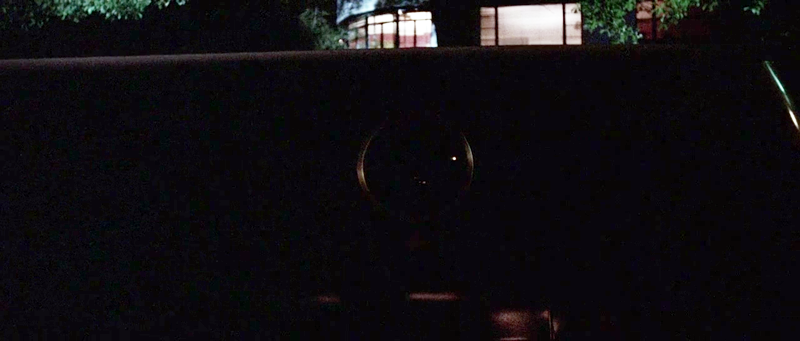

To reinforce the killer’s obsession, Mann uses mirrors in subtler ways: doubling characters, ‘reflecting’ Will’s image in the killers he pursues, duplicating scenes, and mirroring the viewer’s gaze self-reflexively through lenses (and other circular objects like light fixtures and lamps).

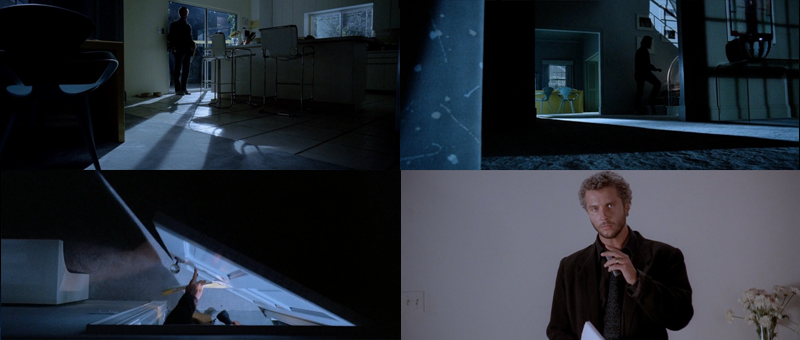

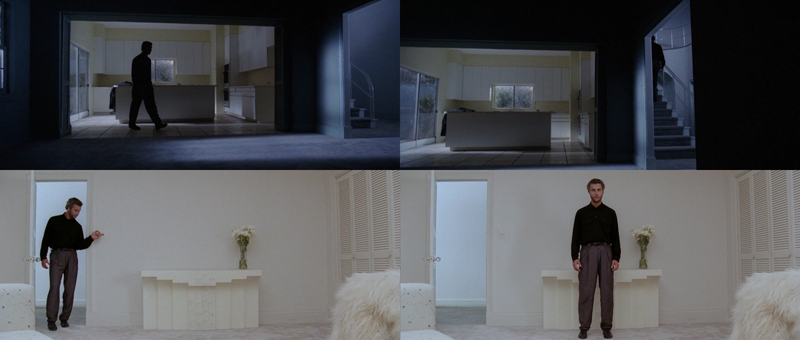

For example, Graham’s crime scene surveys bookend the film. Each sequence ends in the master bedroom, where Graham tries to inhabit, or mirror, the Tooth Fairy’s psyche. During the first survey, Graham is uncertain, probing; during his second walkthrough, he has a moment of revelation. Notice how the perspective shifts between each sequence. In the second, the camera raises from its predatory position behind the furniture. Likewise, the bedroom entry shot first presented from a Hitchcockian overhead view is replaced by a serene, balanced frame accented with the softness of the surrounding furniture and flowers.

We see relationships mirrored between partners, lovers, and again, between Will and the Tooth Fairy.

Characters are fragmented or refracted like the shards the Tooth Fairy uses on his victims.

The Tooth Fairy is ultimately undone when Graham symbolically crashes through the large glass window that surrounds the killer’s home. (Without this symbolic dimension, this scene makes no sense, since Graham loses the element of surprise and realistically would’ve been cut to shreds.) The Tooth Fairy ultimately perishes among the shattered debris.

And finally, we have more metaphorical uses of mirroring and vision through lenses (typically pointed directly at the viewer), lights, and portholes.

Cutting

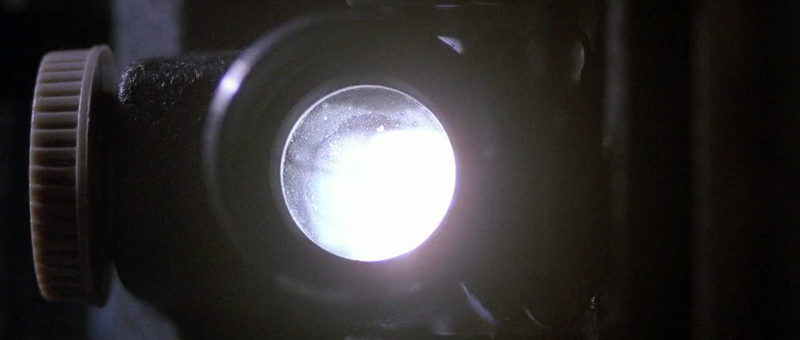

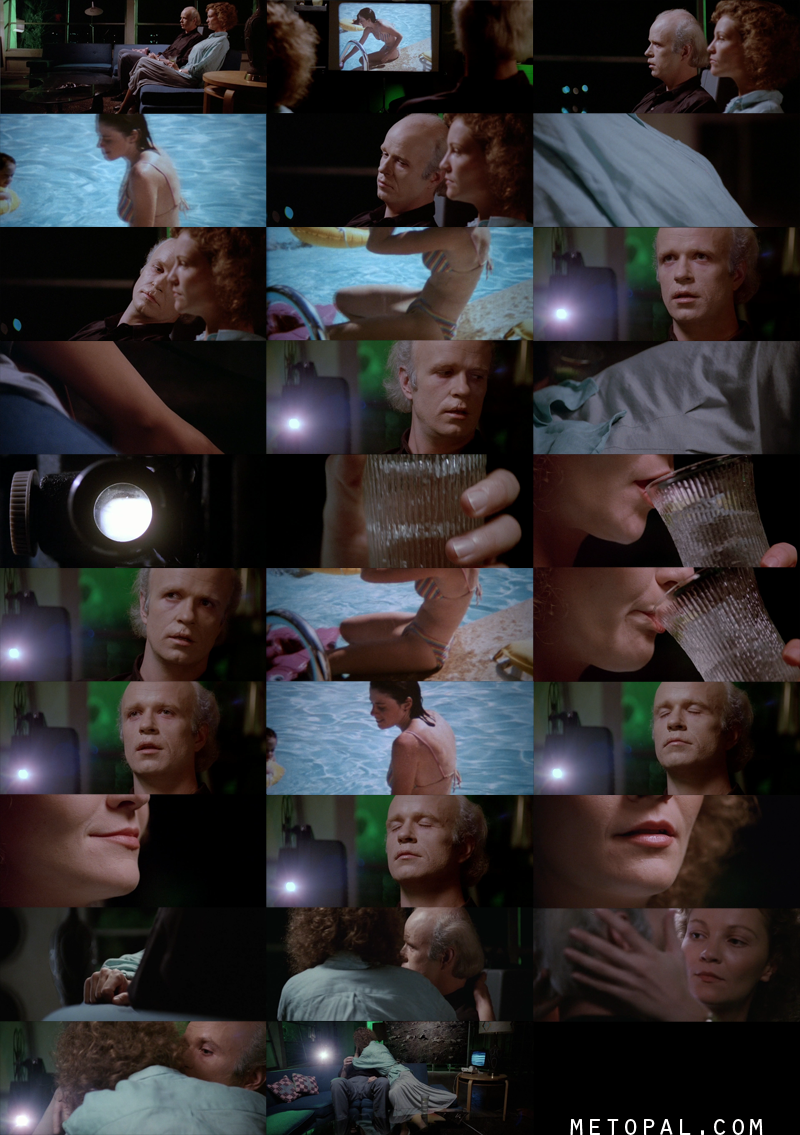

The most remarkable scene takes place between Francis Dollarhyde (the Tooth Fairy) and his emerging love interest, Reba McClane. After a brief and peculiar courtship, McClane returns to Dollarhyde’s home. Drink in hand, she joins him on the couch while he views a home movie of his future victim.

Across roughly sixty seconds and twenty cuts, we witness an eerie erotic moment. Editor Dov Hoenig cuts between close-ups of Dollarhyde, the 16mm film, and portions of McClane’s body. We take Dollarhyde’s perspective as he oscillates between his future victim and McClane’s lips, legs, and breasts, cutting her into sections. The rhythm builds to a crescendo until Dollarhyde closes his eyes in pleasure, only to have McClane suddenly become the aggressor. She sneaks her arm around his back, seizes his head, looks into his eyes (though she is blind), and kisses him. We end on an awkward two-shot, his body stilted and surprised beneath hers. Dollarhyde’s (film) reverie is broken by the reality of the physical, and his discomfort with her embrace is immediately reinforced by a stilted love scene.

Mann and Hoenig enact violence through editing, cutting the body with the lens. Halfway through the sequence, the projector’s illuminated eye stares back at the viewer like Dollarhyde’s mirror-eyed victims. We are implicated in Dollarhyde’s fantasies, because, as Graham says, ‘You’ve seen these films.’

It’s a stunning, disturbing, and beautiful scene, reminiscent of both Hitchcock’s famous shower scene from Psycho and Eisenstein’s groundbreaking Odessa steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin (wherein Eisenstein also used mirrors for visual effect).

What’s lost in the above shot-by-shot breakdown is the stellar sound design—the background music and dialog recede so we only hear the mechanical rattle of the projector and the ice clinking in McClane’s drink—and the hypnotic looping rhythm of the 16mm film, as a series of jump cuts spin the victim’s body again and again for Dollarhyde’s pleasure.

Framing

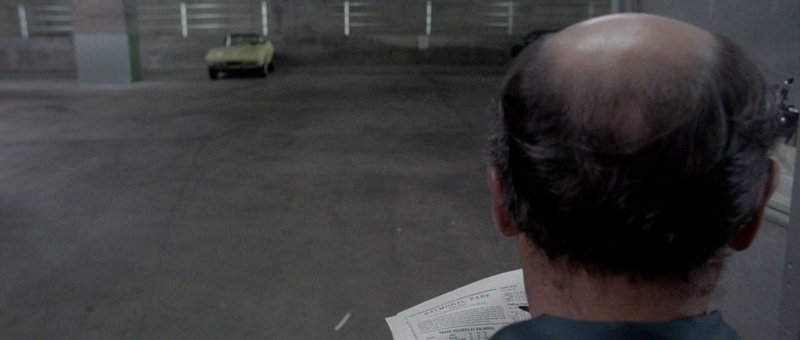

Mann frequently breaks the rules of ‘proper’ filmmaking by obstructing characters with props, shooting the backs of characters’ heads (even during dialog), or otherwise disrupting the frame. Doing so constantly challenges how we relate to the scene and its characters, keeping us in a state of unease, unfamiliarity, and disorientation.

Dressed-up

Manhunter is an impressive visual work, saturated with stylistic sensibilities that elevate it beyond its genre peers. Above all, it’s a standout example of intentional filmmaking. Despite Kehr’s assertions, nothing feels ‘unmotivated.’ Each frame feels carefully considered, lovingly constructed, artfully designed.