Human-Car Affect in The Fast and the Furious

My first foray into Paul Walker studies.

Via Twitter, Ian Bogost recently outlined criteria for the ideal ‘airplane film,’ i.e., a film that can help expedite time’s passage while flying. While length plays an obvious factor in ‘absorbing time,’ as he said, Bogost also emphasized a ‘lack of affect’ as the most important property and highlighted the Fast and Furious franchise as perfect specimen. In lieu of quoting, I Storified the series below (along with an important concluding exchange):

Note: if the Storify embed doesn’t appear below, try refreshing (or go here).

I’d done some similar, albeit less articulate, Twitter musing last summer while I watched the first five films in the series. I did not like them in any traditional sense—I had little emotional attachment to the characters or narrative arc. The script was dull. The music was predictably dated and awful. I am also not a ‘car guy,’ so the race sequences felt about as emotionally thrilling as a Gran Turismo replay. But nonetheless I found the series riveting.

Exposed engine. Custom rims. Nitrous. Fins. Techno. Car-being.

— Nathan (@circuitlions) June 16, 2013

I agree with Bogost’s conclusion about airplane films, but I want to extend and diverge from his tweets at two points: first, his agreement that Crash is the F&F endgame and second, F&F’s status as an affectless film. (And let’s keep in mind that I’m responding in long form to a bit of Twitter riffing, so I’m not holding anyone to any grand theoretical conclusions. Consider this an extended riff.)

Point one: Though I understand Crash’s appearance in the conversation, I disagree with Omoto’s conclusion. F&F’s human agents are not in love with machines. There is certainly prolonged fawning over engines, parts lists, upgrades, modifications, and performance machines. Vehicles are shot lovingly, especially prior to street races, when cars and their owners participate in an elaborate ritual of preening and exposure, a cross between performance and pornography where hoods are lifted, interiors exposed, and human bodies swarm to touch machines. But I think these pre-race rituals are more than a sublimated libidinal urge to fuck cars (or even a less sophisticated metaphor for, ahem, sex drive). Instead, humans bodies in Fast and Furious want to be car bodies, or at least revel in a liminal state of Deleuzian car-becoming.

Baudrillard had a similar read on Crash in an article of the same name from Simulacra and Simulation. Here, the automobile accident creates new assemblages of machine and flesh: ‘Body and technology diffracting their bewildered signs through each other. Carnal abstraction and design. No affect behind all that, no psychology, no flux or desire, no libido or death drive’ (112). Again, the endgame is not sexual or violent release, but a delirious vortex of circulating bodies, what Baudrillard calls a ‘*nonperverse* pleasure.’ ‘Bodies and technology combined,’ he writes, ‘seduced, inextricable.’

The girlfriend can offer herself in lieu of a pink slip because in #TokyoDrift human and car bodies are equivalent.

— Nathan (@circuitlions) June 18, 2013

Observe how bodies are treated in F&F: decked in the chrome of turn-of-the-century raver culture, chains dangling, buckles shining, spikes protruding, piercings lining their flesh. Women especially (and problematically) are profiled like cars, from the tires up.

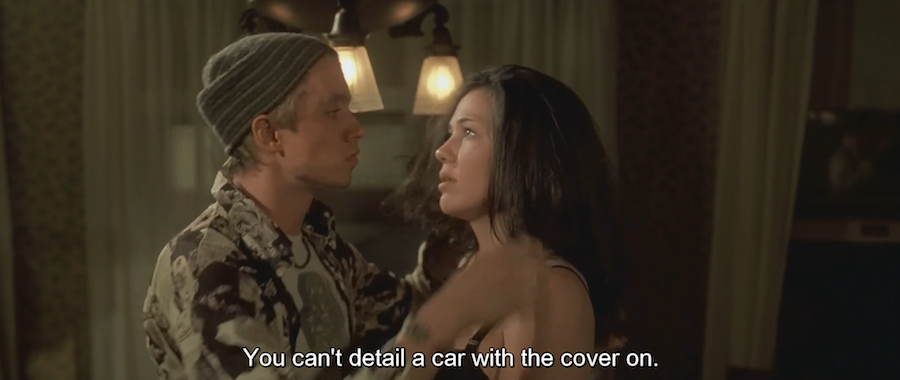

Humans speak of one another as if they are cars: Dom scolds Jesse for trying to ‘detail a car with the cover on’; Letty threatens to ‘leave tread marks’ on a pair of girls’ faces after they flirt with Dom; Tej asks Suki when she is going to ‘pop his clutch’; and so on.

While these phrases come off as bad metaphor and innuendo, note that the promises of sex and violence are never consummated ‘in the flesh.’ Jesse doesn’t remove his ‘car’s’ cover (he continues cavorting with her downstairs). Letty never fights. Tej and Suki get no sex scene. When Brian and Mia finally hook up, we only observe the affectless afterward, with Brian crawling out of bed shirtless (notably after the camera tracks through a menagerie of car parts) so he can return to his body’s true motivating purpose: driving.

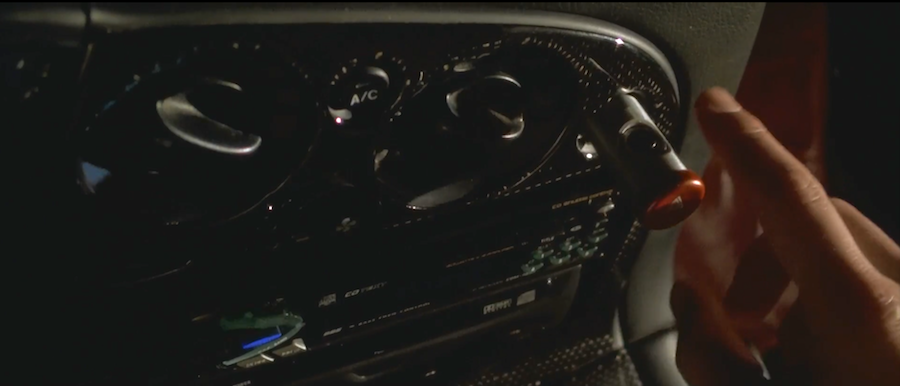

Sex is only referenced via car bodies—especially through NOS, the seminal wonder fluid that blurs the reality of any time or space beyond the car interior. Through NOS, not human but *car* desire is manifest. NOS is the car’s titillating secret, always hidden beneath hoods or seats, accessible by pressing two red buttons (use your imagination) or, most overtly, when Dom’s car presents its NOS control as a protruding rod.

When NOS engages, we’re treated to a fantastic fly-through of an impossible CGI carscape of pistons, fans, gears, and fuel flow.

Point two: F&F are not affectless films. I agree with Bogost that the human relationships are devoid of affect, but I suggest that this does not drain the film of affect altogether, but rather transfers human-human affect to human-car relationships.

I’ve hinted at this idea in the examples above, but it’s worth a moment to explain what I mean by affect. This is a loaded term in philosophy, one that has triggered a so-called ‘affective turn’ in theory circles, accompanied by the requisite deluge of academic books and articles. I’m not sure if Bogost was referencing the term in a general or theoretical sense (again: Twitter), but I’m lifting my usage from Deleuze and Guattari in What Is Philosophy? It’s one of my favorite philosophy texts because D+G are grappling with what it means to be a philosopher, how philosophy fits in among art and science, and what it is that philosophers create (spoiler: concepts).

But beyond philosophy, D+G also explain what artists are up to, namely that they create and present affects. So what is an affect? Generally, it’s a sensation of vibrant in-betweenness. They write:

The affect is not the passage from one lived state to another but man’s nonhuman becoming…becoming is neither an imitation nor an experienced sympathy, nor even an imaginary identification. It is not resemblance, although there is resemblance. But it is only a produced resemblance. Rather, becoming is an extreme contiguity within a coupling of two sensations without resemblance… (173)

The F&F films are saturated with an ‘extreme contiguity’ of human and car, what D+G would describe as a becoming—’passing one to the other’ in a ‘zone of indetermination, of indiscernibility.’ 2 Fast 2 Furious illustrates this best in its opening race scene where its cars and humans are decked in matching colors.

The drivers do their best to merge with their car bodies. Likewise in the posters for the first two films—blurred car bodies emerge in brilliant color amidst strange human hydras, flattened in grayscale.

So if Crash is not the Fast and Furious endgame, what is? The films themselves suggest two possibilities: One is an eventual inversion of the human-car relationship via videogames. In the first film, we witness a (stereotypically Asian) driver playing Gran Turismo on an in-dash screen as he waits for the race to begin.

Letty later repeats this scene at the house party, but the game screen admonishes, ‘Wrong Way.’ The refraction of the medium within the medium only works in-car and only with early racing games like Gran Turismo, where the cars were tinted, driverless shells. Pure affect, pure texture, flesh forcibly expelled from the car body to experience it both within and without simultaneously.

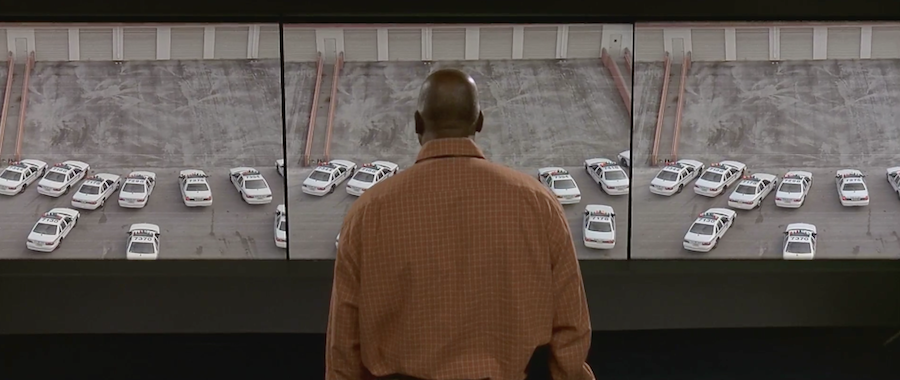

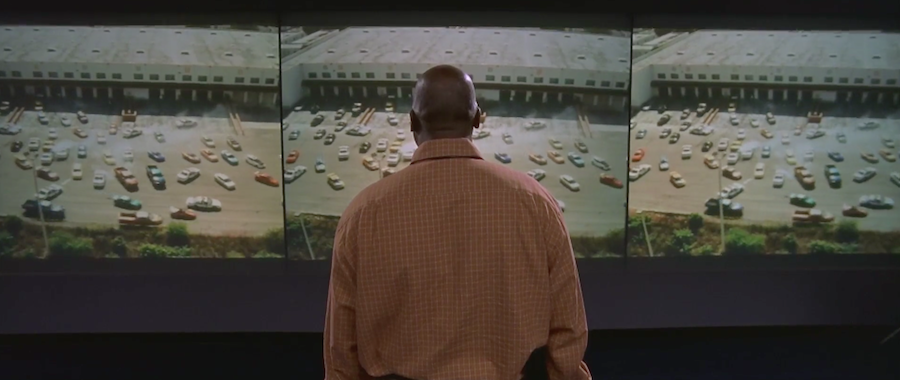

The second possibility is 2 Fast’s penultimate action sequence. To evade their police overseers, Brian and Roman orchestrate a car ‘scramble.’ They enlist dozens of drivers to hide away in a warehouse, lure the cops outside, then escape unseen in the scramble—a flood of endless cars spilling from the interior.

#2Fast can not contain its own car excess. Infinite cars spill forth from a garage, pure car immanence.

— Nathan (@circuitlions) June 17, 2013

If 2 Fast were to fulfill its affective promise, it would end with this scene. Or better, a locked groove of vehicular plenitude, this joyful outpouring of car-being.

This scene is not just a visual spectacle but an invitation to participate in car becoming. To emphasize the point, we see two shots of Agent Bilkins, the camera positioned behind his head, observing the scene in triplicate, first when the warehouse is closed and later when the torrent of cars begins. When the camera swings to frame his face, he smiles at us.

And this is the joy of Fast and Furious that eludes conventional criticism. It isn’t a matter of liking or disliking the films according to their technical acumen or storytelling or even their car showcasing. It is a question of participating in its peculiar affectivity. As D+G say, ‘It should be said of all art that, in relation to the percepts or visions they give us, artists are presenters of affects, the inventors and creators of affects. They not only create them in their work, they give them to us and make us become with them, they draw us into the compound.’