Fantômas

The master of disguise. The heist. The narrow getaway. The obsessive police inspector. The inside man. The prison note. The body double. The last-minute escape from execution. 1913 French serial Fantômas hits all the beats of a modern crime thriller, but its pace and plotting are so divorced from modern conventions that it is hard to group it alongside contemporary films like Mission: Impossible or Ocean’s Eleven.

Fantômas I: À l’ombre de la guillotine (In the Shadow of the Guillotine) was the first of five hour-long features directed by silent film pioneer Louis Feuillade and released between 1913-14. The character Fantômas was based on a popular series of assembly line crime novels of the same name written in France in the early twentieth century. According to Wikipedia, Fantômas was a peculiar kind of anti-hero:

Fantômas was introduced a few years after Arsène Lupin, another well-known thief. But whereas Lupin draws the line at murder, Fantômas has no such qualms and is shown as a sociopath who enjoys killing in a sadistic fashion. He is totally ruthless, gives no mercy, and is loyal to none, not even his own children. He is a master of disguise, always appearing under an assumed identity, often that of a person whom he has murdered.

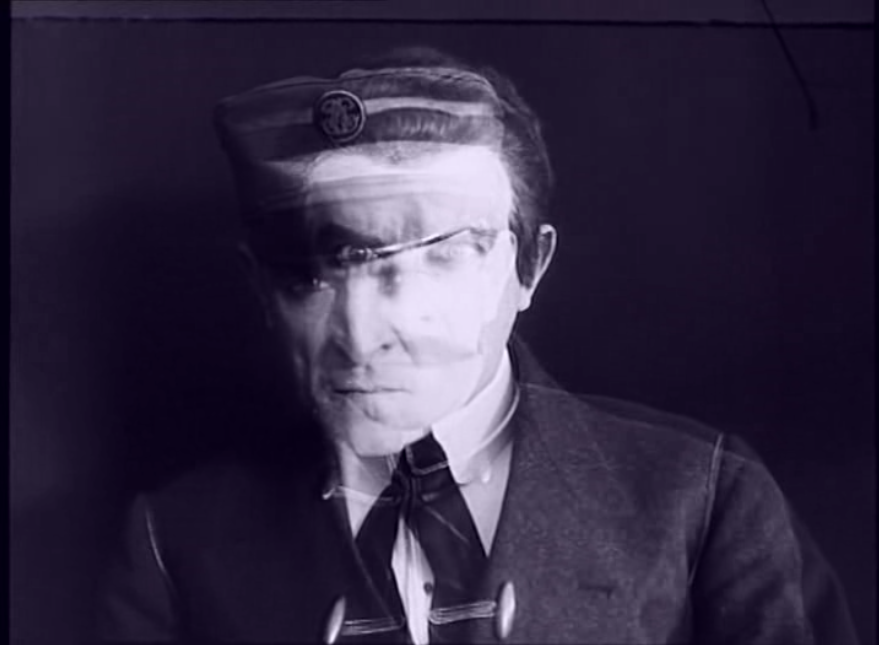

Feuillade leads the viewer to similar conclusions in the film’s prelude, where we are introduced to Fantômas in a fantastic sequence of cross dissolves. He leers at the camera as his face fades slowly through several disguises. His expression is sinister, as if he is directly threatening the film audience.

After the final fade, Act I begins, wherein Fantômas stages his first crime: a robbery. Here we see Fantômas step plainly into his victim’s view, set her down gently on a couch, and (presumably) reassure her that he intends her no harm. This gentlemanly thief appears at odds with the disturbing profile we saw in the opening montage. But as the film proceeds, this small hint of civility falls away. Fantômas kills a man and takes the widow as his mistress and accomplice. To free himself from prison, he has no qualms framing an innocent man and leaving him to die in his place. With little context for his crimes, Fantômas comes off as a ruthless rogue.

The subsequent hour’s plot is skeletal. In Act I, Fantômas robs a wealthy woman in a hotel (demonstrating his proclivity for hiding behind curtains), then narrowly escapes by swapping clothes with an incapacitated bellhop. Act II foregrounds Inspector Juve, who discovers the grisly murder of Lord Beltham (a character lifted from the novels). The investigation leads him to Fantômas’s true identity, a man named Gurn. Juve eventually locates Gurn, apprehends him outside his home, and triumphantly sends him to prison.

Fantômas’s incarceration sets the stage (quite literally, as we’ll see) for a clever escape in Act III. With the assistance of several co-conspirators, including Lord Beltham’s widow (who is also the criminal’s mistress), Fantômas manages to climb out of a prison window, drug the actor Valgrand (who is portraying Fantômas in a stage play of his impending execution), and hasten the captured man back to Gurn’s prison cell. On the day Fantômas is meant to face the guillotine, Inspector Juve discovers that Valgrand has been framed and that the true murderer/thief is still at large. The film ends in true serial fashion–with a cliffhanger. A title card tells us that Juve is now obsessed with capturing Fantômas and we find the Inspector alone in his office. Suddenly, a ghostly Fantômas appears in the room, taunting Juve to cuff him, only to disappear again as Juve tries to restrain him.

Despite the quantity of plot described above, Fantômas moves at a glacial pace. The action advances in fits and starts between loosely-associated scenes that often span several days or weeks of diegetic time. Act I’s eleven minutes track the setup and execution of the hotel robbery, but significant chunks of screen time are spent lingering on inessential details. For instance, Feuillade has a strange fascination with the hotel elevator, tracking its path to and from the lobby, lodging the camera at each floor, while the actual chase occupies a few spare seconds. In other scenes, we see the same preoccupation with extraneous activities: a car pulling into a driveway, passing letters between characters, or Valgrand putting on his stage makeup. Coupled with the static camera that rarely pushes beyond a two-shot, the ponderous scenes make for difficult viewing.

Certainly the pacing is a token of the film’s age, but it also speaks to the shifting expectations and patterns of editing over the past century. Montage is the lifeblood of cinema, cutting through space and time to assemble disparate images, characters, and locations. Save for violating the laws of physics, film makes possible what our eyes could never see. What we find in much early cinema is editing as a spatial practice. The cut conveys the viewer through space, largely linking locations in chronological sequence. Editing as a temporal practice, in contrast, performs the inverse function, linking distinct slices of time across space.

Consider Feuillade’s fixation on the elevator. He uses the camera to literally take the viewer upstairs, traveling alongside our victim to the scene of the impending robbery. At each floor, the camera sits in a similar position, holding the elevator near the center of the frame. A sign on each floor marks our progress. It is a clear visual clue to the audience that we are moving through space.

Such cues seem overbearing now, but as I’ve written before, in the early decades of the twentieth century, cinema was still shaking free from the conventions of stagecraft. The camera provided a front row seat for a new kind of play, one that could transport the viewer to multiple unconnected sets. Imagine a hypothetical theater with seats positioned on a moving track that could move instantaneously from scene to scene without having to re-dress the same stage. The camera and the edit stood in for this imaginary theater.

The fixed perspective was likely reassuring to viewers who were new to film. In fact, we see frequent instances in early films of ‘doubling’ the stage to reinforce the effect. In Act III, for instance, we see Valgrand onstage, in his Fantômas ‘disguise,’ performing for a packed house. The camera is parked far enough back that it shows the frame of the stage and several rows of audience. What’s fascinating is that the scene portrays multiple doubled identities: Valgrand, disguised as Fantômas, doubles the role of the thief, who in turn is a kind of actor, since he too is a master of disguises (and is also portrayed by real-life actor, René Navarre). Valgrand performs the criminal’s final moments in prison, including the constables’ entrance to escort him to the guillotine. As he leaves, the curtain falls. Here, Feuillade has rehearsed the apparent finale of the film in a fabricated prison set that simulates the film’s own prison set seen earlier in Act II. Part of the thrill of Fantômas’s escape is the viewer’s knowledge that the execution has already taken place. By staging the play-within-the-film, Feuillade has cleverly both killed and saved our criminal mastermind.

In a related scene, the camera is pulled further back, behind Lady Beltham, who watches the stage play from a private box. Her elbow rests on a small balcony that frames Valgrand’s performance, once again doubling the same film projection we saw seconds before. She then turns her head toward the camera as if to implicate the viewer in this charade. She is clearly troubled about the plot that is about to take place. She knows Valgrand does not deserve to die in Fantômas’s place (as he does now on stage) and by moving her gaze to the camera, she makes us complicit in the same crime. By watching Fantômas, we allow the double framing to take place.